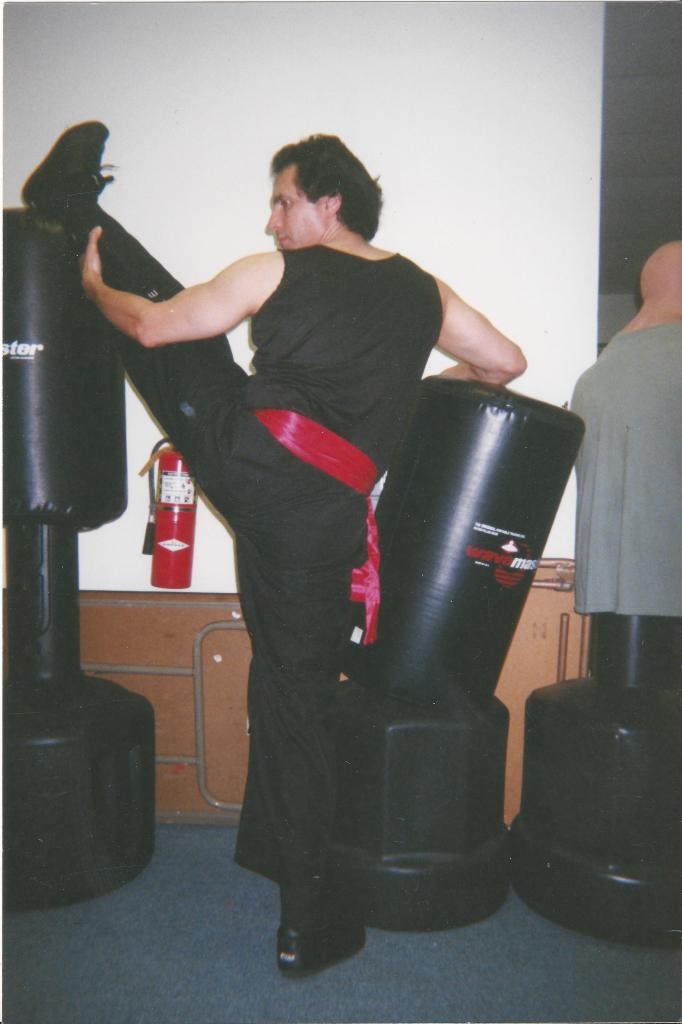

“So what have you heard about me?” Diane Reeve asks. This isn’t her first interview; she originally told her story on 20/20 and then twice on The Oprah Winfrey Show. Diane owns her own martial arts school in Plano, Vision Martial Arts, where she spends her autumn years teaching people roundhouse kicks and kata forms. She jokes that she fell in love with the sport because she likes hitting people, but Diane’s main passion is empowering her students. Barely five feet tall, she’s an eighth-degree black belt and the leader of an all-female black belts demo team. Their uniforms are emblazoned with “Dracarys,” the battle cry of the Mother of Dragons from Game of Thrones. She and her squad of black belts are known as the Badass B**** Club.

She hands over a copy of her book, a hot pink paperback, Standing Strong, which she and Ghostwriter Jenna Glatzer published in 2016. “Everyone always told me I should write a book about everything that happened, so I finally did. It’s pretty honest, but the editor cleaned up some of my language.”

Standing Strong opens with, “That son of a b****!” Clearly, the editor had her work cut out for her.

“I guess you want to hear about Phillippe, huh?” she says with a fixed stare. She curls her legs up onto the armchair to make herself comfortable. Telling her story will take a while.

At the end of the date, he promised he’d call. “You can trust me,” he added.

Plano was a sleepier, smaller place 15 years ago. Though it wasn’t a farming community anymore, the sprouting neighborhoods were still peppered through with farms, each with a founding family name on the plot: Wells, Haggard, Hendrick. The Shops at Willow Bend was a novelty, only two years old, and so was the DART service at downtown Plano. In one year, Money Magazine would name Plano the number one hottest city in the West with a population over 100,000.

Diane had already lived a full, vibrant life in Plano before Philippe Padieu became a part of it. She had been married and divorced twice and still wanted to find the love of her life, so she joined Match.com. “And then I met Philippe.” She rolls her eyes. “Talk about a return on my investment.”

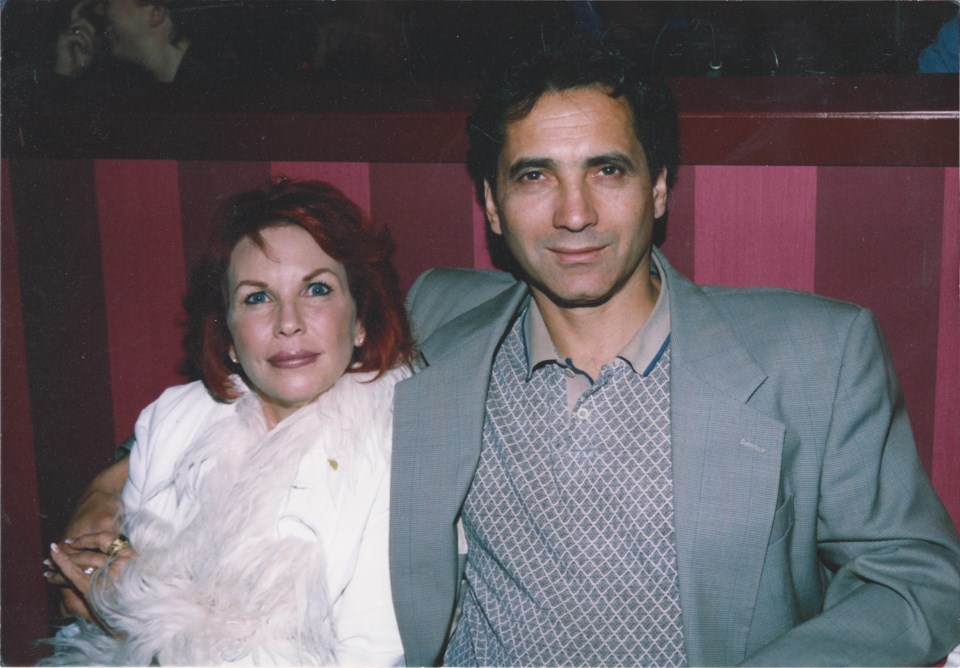

When a handsome French man sent her a polite, if generic, message, Diane was intrigued. His name was Philippe and he seemed straight out of an advertisement: slender with thick dark hair, darker eyes and a charming smile. It was kismet: he had a successful career, loved adventure, and, like her, he practiced martial arts. He seemed lightyears above the other men whose profiles she’d flipped through. They met at her martial arts school for their first date. She’s never forgotten his black western boots.

“We went to Chili’s for appetizers and drinks,” Diane recalls. “I thought of him as a French cowboy.”

At the end of the date, he promised he’d call. “You can trust me,” he added.

Looking back, Diane scoffs. “What bull.”

“This is your fault.”

Over the course of their ensuing relationship, Diane came to know more about Philippe than anyone. But even now, the details are like strange jigsaw pieces that don’t come together into a conclusive picture. They leave more questions than answers. Philippe was born to a 19-year-old mother and an absent father, raised by his grandmother in a post-WWII camp in France. He described to Diane Dickens-esque early years, living in a shack with dirt floors and bare cupboards. One day, his pet rabbit disappeared and that night, they had meat in their stew for the first time in weeks—that was the kind of poetic, gripping tale Philippe loved to tell. He reminisced about his first love, a young angelic girl in the camp who, like the rabbit, vanished one day. Though he never knew what her fate was, he suspected that she died of malnutrition. Even 30 years later, recounting it in Diane’s arms, her memory brought tears to his eyes. After a muddied childhood in France, his mother and her new American soldier husband moved them to inner city Detroit, where Philippe, desperately unhappy and unwanted, learned martial arts in order to survive.

Philippe was a captivating storyteller with a knack for tailoring the truth to make himself the hero, the underdog and, often, the victim. He had one felony on his record from his time in the U.S. Navy. He and a friend were caught jumping other servicemen leaving the base with cash on payday. Even then, he was the true victim, a product of a dysfunctional childhood who was lead astray by a morally bankrupt friend. By the time he met Diane, he was stable, if unlucky in love, with a good job as a network security analyst in Texas.

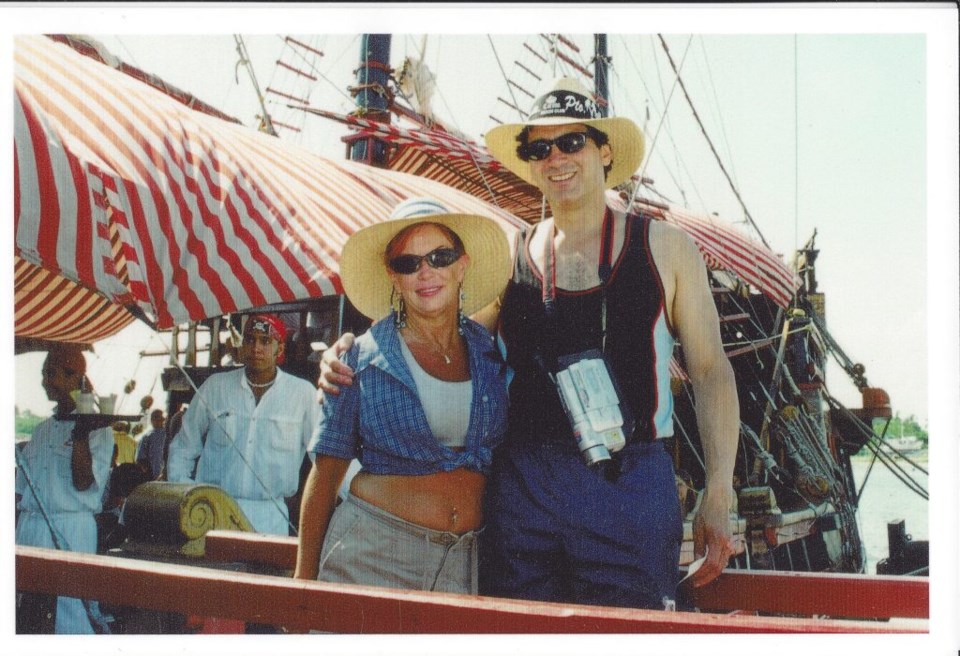

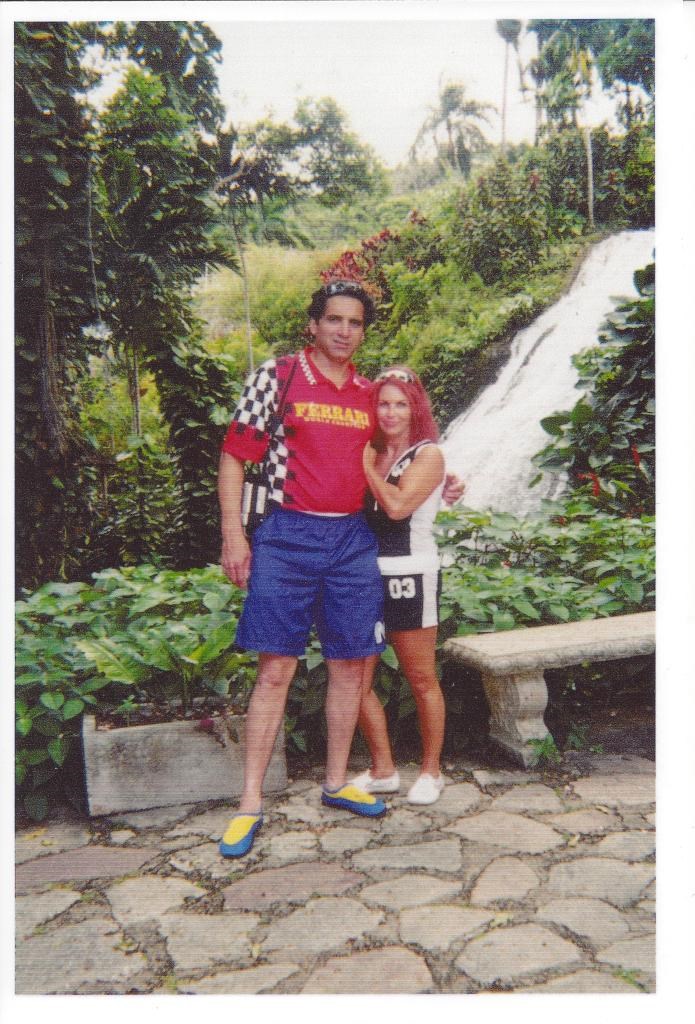

“He swept me off my feet,” Diane recalls. “We were together for four and a half years. We’d discussed exclusivity, talked about STDs—everything was fine. We traveled the world together: Paris, Rome, Jamaica. We laughed together. Looking back, there were a couple of red flags that I missed or just chose to ignore. I was 50. I put up with a few things because I thought it was probably my last shot at love. And I loved him.”

Philippe poured his heart out to Diane. But at the same time, 15 years later, Diane knows that he offered her nothing at all.

“Now I know the signs of sociopathy and narcissism. I can look back and blame myself,” she says and shrugs. “But I’m never sick of telling people not to blame the victim. I think that our society does that because if you can find something wrong with the victim, you can point fingers. It’s a fear-based response. You can say that’ll never happen to me because I’m smarter, stronger, faster. It makes us feel safer and that’s why it’s hard for victims to come forward: you already feel so stupid. Let me tell you, I felt stupid. How could I have been so blind?”

It all fell apart in 2006. They were in the process of buying a house together in Allen, but by then, the cracks had begun to show. Odd things had begun to raise questions in her mind: why did his two twins, who lived in Detroit, practically disown him? Why did Philippe insist she could never leave anything of hers at his home? Even today, Diane can’t explain why this was the final straw. He’d cheated on her once, two years in, and she’d forgiven it. But when Philippe skipped a family dinner after her daughter’s wedding, claiming sudden illness, Diane had had enough.

“I drove by his house to check on this poor, sick man,” she scoffs. “And he wasn’t there.” Philippe had recently been laid off and Diane had offered to pick up the tab for some of his expenses, such as his cell phone. Though it wasn’t her proudest moment, she looked up his call history. She found two different voicemails from two different women, who both seemed to be dating Phillippe. While Diane listened, Philippe’s sleek black Corvette pulled around the corner. He saw her and stopped. Diane stared at him; he stared back.

“If this were a movie, this scene would be the car chase,” Diane says wryly. Philippe tore off down the street and Diane roared after him. They raced down the Dallas North Tollway, edging toward 90 miles an hour. “I was devastated. I was upset and angry, but I was going to have my say. I was thinking, ‘I can do this all night. I’ve got a full tank of gas,’” Diane remembers.

Finally, Philippe yanked off the road into a stop. She pulled in behind him and he stalked over to her car. The man who greeted her, expression tight with rage, was like a stranger. “This is your fault. You listened to the voicemails, didn’t you?” he snapped.

“Turns out, he’d been seeing, off and on, nine women,” Diane says. “Some were one-night-stands, some were two or three dates in, one was six months—he hadn’t been seeing any of them as long as me.”

“No one was safe.”

In the aftermath of the messy, bridge-burning breakup, Diane discovered that Philippe had given her HPV, which had caused a precancerous condition. She reviewed his cell phone records and starting going down the list, warning every woman who answered that he’d given her an STD and they needed to get tested. As she did, she began to learn more about his secret life.

“He had it all worked out. He saw me on Monday, Wednesday and Saturday—when he taught at my school. He saw another woman, referred to in the book as “Susan”, Tuesday and Thursday. Friday was his swing night. Sundays were reserved for one night stands.” Even during their relationship, Diane had been a little suspicious about the rigid schedule. “Sometimes I used to plan things on purpose on the wrong nights—on a Thursday instead of a Wednesday. He never batted an eye.”

One of the women, called Susan in the book for anonymity, asked Diane to meet. It was a thoroughly awkward encounter, both sizing each other up. Over drinks, Diane told Susan about her relationship with Philippe and Susan listened carefully before saying that she and Philippe weren’t exclusive and she wasn’t quite ready to pull the plug.

“I told her, ‘Hey, take it for what it’s worth, I don’t want him,’” Diane recalls. “I actually said, ‘It’s your funeral,’ which almost came true.”

Not six weeks later, Diane got a call from Dallas County Health and Human Services. Someone had given them her name because she had possibly been exposed to an STD. “They wouldn’t tell me why or who gave them my name,” she says softly. “So, I knew something was very wrong.” She hadn’t been with anyone but Philippe in over four years. But she tested positive for HIV.

Diane offers a sad half-smile. “That’s when I knew I was going to die.”

“It’s your funeral.”

For a long time, all Diane could do was suffer as she grew steadily weaker. Every day, she felt herself lose a little more of her vitality; she describes it as a never-ending case of the worst flu one could ever have. Strange white patches popped up inside her mouth. Because HIV prematurely ages those who have it, soon she began to wear her diagnosis on her face.

Diane, independent and proudly so, was used to having control over her body. On the mat, she was David and her opponent was Goliath. It didn’t matter how many inches, pounds and muscles they had on her; she was used to an opponent she could fight. Her body had always been her finely-tuned weapon and now it was a struggle to lift her head off her pillow. She couldn’t stop thinking about the the virus eating away at her brain and kidney cells. She hardly recognized herself.

“Here are the two most important things you need to know about HIV,” Diane interjects. “First, if your viral load [how much virus is in your blood per milliliter] is low enough that it’s undetectable for six months, and if you’re consistent with your medicine, you are incapable of passing on the disease. There’s a big campaign about it: Undetectable equals untransmittable. Second, the words we use to describe HIV differentiate it from any other disease.” Diane has now been living with HIV for close to 15 years.

“In Africa, HIV is a health issue, a medical issue. In America, it’s also a social issue,” she explains. “We don’t say ‘measles-infected’ or ‘flu-infected’. Do you hear anyone saying ‘diabetes-positive’? ‘Kidney disease-positive’? No other illness has that ‘plus’ sign with it. It sets us apart.” When she was first diagnosed, outside of her family, closest friends, and the other women involved in the case, no one knew that Diane was living with HIV. She was terrified about what would happen if her diagnosis got out, picturing an exodus of her students from her school. One of Philippe’s other victims once remarked that she would rather have had cancer than HIV. “At least I could tell people I had cancer,” she said.

Thanks to her medication, Diane has been undetectable for 13 years. But in the months immediately after her diagnosis, she couldn’t afford medication and it wasn’t covered by her insurance plan. Though she was still reeling from the revelation, the virus was so advanced that her doctor suspected she had contracted HIV at the beginning of her relationship with Philippe. They were shocked that she wasn’t exhibiting more symptoms.

If Diane had HIV, Philippe had given it to her. She thought of Susan, the kind, soft-spoken woman who had also been taken in by him. When Diane called, Susan admitted that she had also been diagnosed with HIV. In fact, she had been the one to give the health department Diane’s name.

“So, I asked her if she’d talked to Philippe, if he knew,” Diane says. After a moment of hesitation, Susan said that she had reached out to him and their conversation had been strange.

Philippe hadn’t been at all bothered by the knowledge that he was living with HIV. All he said was, “Everybody dies of something, so why don’t you just go live your life?” But when Susan let slip that she had given Philippe’s name to the health department, he blew up at her, screaming that she was trying to ruin his life. Later, she emailed him asking how many women he’d transmitted to and he’d replied only that “they” would never find a common denominator.

“That was weird to us,” Diane explains. “I mean, I found out and I cried for days. I was saying goodbye to my family in my head. So his reaction—that didn’t strike us as someone who didn’t already know.” She and Susan began to wonder if he’d known all along. Philippe never wanted to use condoms. He’d promised Diane, Susan and more women that he was “clean.”

They went to the police a week later. The officer who took their report was sympathetic but before long, told both women that unfortunately they didn’t have a case; there were only two of them.

“Fast forward to Bill Cosby, Roger Ailes, Bill O’Reilly, Harvey Weinstein—today, we see that one person comes forward and then the floodgates open,” Diane says. “This was 2007. This was before #MeToo or #TimesUp.” The officer suggested that if they had four or five women making the complaint, the DA might take a look at it.

“I'm negative.”

Diane and Susan didn’t have to search for long before finding more women who had been with Philippe and had no idea they were living with HIV. The third victim they found is referred to as Maggie in the book, a single mother and his neighbor. She also had HIV. Maggie watched the stream of women coming and going from his place, writing down descriptions and their license plate numbers. Diane had a friend with access to the DMV; she and Susan tracked each woman down to warn them about Philippe’s true nature and ask for their help. It was a grueling full-time job none of them ever wanted. But the more they learned about Philippe’s partners, the stranger he became and the larger their pool of survivors grew. They formed a support group to console each other.

“No one was safe,” Diane explains. “All of the women were very different. He didn’t have a type. We were anywhere from age 23 to 64, every race, every size, large women, small women, blond, brunette, redhead—no one was off limits. I was a Texas girl, one was from Mexico City, another from Cairo. I can remember every time we met, someone in that group would have a meltdown.” Two of the women were connected to Diane’s school. One was a student at the martial arts school, married with kids, and another was one of Diane’s close friends, whose three sons were all students. One woman had severe mental issues and another had multiple sclerosis. Philippe referred to her as “the cripple.”

Whatever healing they found came from banding together. They saw each other not as romantic rivals, but sisters. It was life-changing to see that they weren’t crazy. They weren’t alone. They’d all been conned. Maggie watched Philippe’s revolving door of women, which hadn’t slowed even after Susan had told him about her diagnosis. It reminded them all to stay strong: they weren’t the ones at fault.

“I formed the group to help them, but they really helped me,” Diane says.

Even now, the stress of those months shows in her eyes. “I was in fear of my life, not only because of HIV, but also because if Philippe found out what we were doing, that we were planning to take him to court, he would have killed us.” He’d already made threats, telling Susan to be careful, because “The knife cuts both ways.” One day while Maggie was pulling weeds in her front yard, he stormed across the street and slapped her in the face.

Though Diane’s doctor insisted that she would survive, Diane endured months of falling T-cells—also known as CD4—which are in charge of immune system functions, and an ever-rising viral load. She couldn’t afford the $2,000 a month prescription. At its worst, her CD4 count, which for a normal person is between 500 and 1500, was 31. Her viral load, which was supposed to be zero, was over 1.2 million. At that point, she received a second diagnosis of AIDS. Her doctors were stunned that she was still functioning, let alone leading a crusade against the man who’d betrayed her.

By the time Diane finally qualified for a special high-risk insurance pool and got her medication, she had kidney damage. But she was determined not to be broken.

“I still thought I was going out, but I was going out fighting,” she says. As they kept collecting evidence against Philippe, he noticed them, even if he didn’t know what they were after.

“He complained to the police that we were out to get him.” She smirks. Even years later, justice is still sweet. “I guess it’s not paranoia if it’s true.”

In order to prosecute Philippe, it wasn’t enough to prove he had been transmitting HIV. Even testimony that he had refused condoms wasn’t enough. They had to provide evidence that he’d known he was HIV-positive. “There was six of us who filed charges and one of him, but we still had to prove it,” Diane says.

Philippe had made one huge mistake. In 2005, he had gone to the doctor for what he said were kidney stones and ended up being called back into the office. Worried, Diane drove him to the his appointment and since he had no health insurance, she paid the bill. While she waited outside in the parking lot, his doctor told him that he was HIV-positive, walked him through the diagnosis and emphasized the responsibility he had to inform and protect any future sexual partners. According to this doctor’s testimony, Philippe didn’t bat an eye. Later, he also met with a representative from the Dallas County health department, and insisted they meet him at an out-of-the-way gas station, instead of their office.

Read more: Finding Christina Morris

“He came back out of the doctor’s office that day and sauntered back to the car, happy as a clam.” Diane remembers it vividly. “I rolled down the window and he said that he was okay, and it had been a simple follow up. And I checked, I listed some of my biggest fears. I specifically mentioned HIV.” Philippe looked her right in the eye and smiled. “I’m negative,” he’d said.

Because Diane had paid that doctor’s bill, the prosecution was able to issue a subpoena for Philippe’s medical records and there was the proof: he had indeed known he was diagnosed with HIV long before Diane and the other women found out. Diane suspects that Philippe knew he was positive before 2005. Two different doctors were able to testify that Philippe had made a habit of refusing HIV tests as early as 2003. The 20/20 interview featured several of Philippe’s former partners, including a woman who he’d transmitted HIV to as early as 1997. Of the six women who came forward to testify, DNA evidence revealed that Philippe had transmitted it to every single one of them.

“I was going out fighting.”

Knowingly transmitting HIV was a strange case to prosecute. It wasn’t exactly murder, though Diane believes that was his ultimate intention. So in 2007, the Collin County DA’s office charged Philippe with aggravated assault with a deadly weapon. He faced anywhere from five to 99 years in prison. The day he was arrested, he spent his one phone call on Diane.

“He actually proposed to me, can you believe that?” she says. “He told me that if I called the whole thing off, he’d marry me. That he still loved me. After everything he’d done, he had the nerve.” She pauses. “I declined.” In Standing Strong, Diane wrote, “I’d sooner set my face on fire with a blowtorch.”

Philippe’s defense team described the women as a hate group. Most of their work in the courtroom centered on characterizing them as spiteful ex-lovers with a shared “if I can’t have him, no one can” attitude.

“It was so interesting to watch the jury.” Diane remembers eight men and four women in the box. “The women came in after every break with their eyes red from crying. A couple of the guys always looked really uncomfortable. But those lawyers tried to get every one of us to call our sisterhood a hate group and failed every time.” Though two of the jurors initially held out for a light sentence of five years, the foreman told them that no one would be leaving until they agreed to a sentence of at least 40 years. Reason and numbers won out and Philippe was sentenced to 45 years, making it a landmark victory, a perpetrator successfully prosecuted using DNA analysis for knowingly transmitting HIV to others.

After news of Philippe’s arrest, more than 10 women and men, all his former sexual partners, came in to be tested for HIV. Though he was only charged by six women, it has been reported that the health department found over 50 HIV-positive women across the U.S., and a number of men, all directly linked to Philippe.

“He’s not even a little bit sorry. There’s no remorse; to this day, he takes no responsibility,” Diane says.

Not long after Philippe’s arrest, a local woman killed her family and then herself. In her suicide note, she warned the police not to touch her blood without gloves because it was contaminated. It’s believed that she had been involved with Philippe too.

“I teach courage for a living. How could I hide?”

Originally, Diane and the others went through the trial under pseudonyms, but in a 2009 20/20 interview, Diane abandoned anonymity.

“I pictured hordes of people screaming ‘Leper!’ Leper!’ when I decided to disclose on national television. But I teach courage for a living. I tell my kids that courage is doing what’s right even though you might be afraid. How could I hide?” Out of over 200 students at Vision Martial Arts, only one parent pulled a child out of her program. Instead of fear, Diane received support from her community. “I was sitting in the school on a Saturday and the father of one of the kids came in wearing combat fatigues. I was sitting at the counter and he walked around and said he wanted to shake my hand. ‘I just got back from Afghanistan and heard your story and you’re the bravest person I know.’ I lost it, right there in front of him.”

After publishing her book, Diane got calls from people on both coastlines and many states in between, from women who had been abused or conned, and some whose partners had knowingly transmitted HIV to them too. Not all of them got justice. One woman, living with HIV in Alabama, had tried to report the crime against her to the police. They pulled out cans of Lysol and sprayed the area around her while she talked.

Today Diane teaches self-defense and acts as a board member for The Turning Point, Collin County’s only rape crisis center, as well as Health Services of North Texas, a nonprofit organization that offers medical care, including treatment for HIV and AIDS. She travels to share her story and advocate for survivors of sexual crimes. She’s open about her diagnosis and passionate about changing social stigmas about HIV.

“It’s not a death sentence but it is a life sentence,” she says.

At her school, famous fighters like Bruce Lee cover the walls. She holds up one picture of her and three tall men, all black belts, including her instructor, the legendary Pat Burleson, who has a hand resting on her shoulder. “See,” she jokes. “He’s got his hand on the most dangerous person in this picture. I thought I was a confident person before I started learning martial arts, but I had no idea what confidence was. It’s nothing compared to my confidence now.” Martial arts has been Diane’s safety and peace through her destructive encounter with Philippe and after. It’s an act of reclaiming her own body, despite what was done to her. She won the fight of her life and not only has she recovered, but she’s deadlier than ever.

“Back then, we were standing up in silence. No one on Twitter was saying ‘Me too.’ For assault victims, there’s a big fear of victim blaming and slut shaming. [After the trial] I was flooded with emails from women exactly like me. I did the right thing, coming forward,” Diane affirms. “I can’t believe the domino effect we’ve seen in the last years with #MeToo and #TimesUp. It just takes one brave person stepping forward.”

Diane thought she’d never trust a man again after Philippe, but recently, she’s tentatively entered a relationship with an old friend. It’s six months along. “He sees me,” she says simply. “Not what happened to me.” She still spends her happiest moments at her school, where now her two youngest grandchildren, three and five years old, have started learning martial arts. Eventually, Diane thinks she’ll transition completely into teaching self-defense. She currently offers training for college-bound students, women, and dads and daughters. She wants to add lessons for people over 50 too.

Read more: Hendrick Scholarship recipient Hannah Aziz

She keeps everything related to Philippe locked away in her “boxes of evil”. They’re full of old pictures of her and Philippe from their best times, on the trips they took together. She digs them out mostly for press inquiries and the occasional book promotion. Recently, she opened the boxes and found an unopened letter from Crime Watch Daily, the news channel that interviewed Philippe while he was in prison.

“I wish they [would] burn in hell, especially Diane,” Philippe told them from behind bars in their 2016 interview. He still claims that Diane was the one who transmitted HIV to him, not the other way around, despite proof that he had transmitted it to others long before he even met Diane, at least as far back as 1997. Crime Watch Daily sent Diane a full transcript of their conversation, in which Philippe ranted about the massive conspiracy that got him thrown in jail. According to him, even his own lawyers had been conspiring against him.

“I’d never read it. I didn’t want to know what he was saying back then. I’d had enough of his lies, so I just put it in a box and forgot about it,” Diane says. “Well, this time, I opened it. I read it and I laughed.” Nothing Philippe says can hurt her now.

Originally published in Plano Profile’s August 2018 issue.