Mom

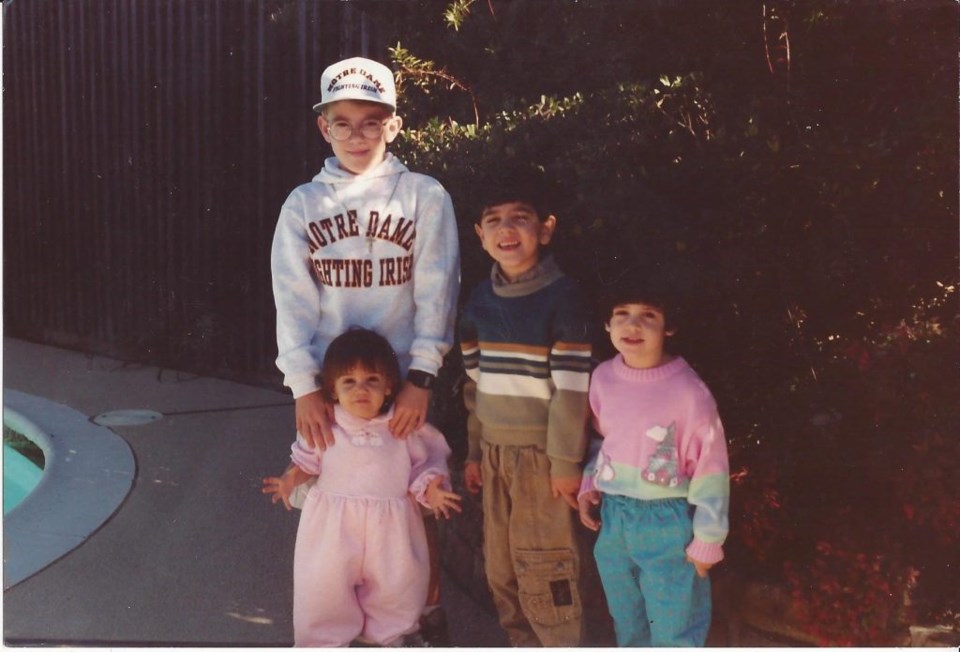

The last time Hannah Aziz saw her mom was Mother’s Day 1993. It was a warm May day in Coppell, and she was three years old. Her memory of it is a patchwork of vivid scenes, sounds and what she’s been told by her siblings over the years. She knows that her mother was leaving her father for good and taking the kids with her. Her two older brothers, Joshua and Ethan, and her sister Bethany were already waiting in the car, seat belts buckled. Inside the apartment, Hannah’s mother held her tightly, arguing with her father. Furious, he shut the door and locked it. Hannah remembers their mingled voices over her head, growing louder and louder.

Then her father shoved them to the ground. Hannah tumbled out of her mother’s arms. He took her mother into the bedroom, leaving Hannah on the floor. They didn’t come back, but she could hear them fighting. At one point, Hannah walked over to the bedroom, where her parents were. Her father saw her and rushed over to pick her up. He put her outside and closed the door. It was the last time either of her parents would ever hold her. Her father had gone back inside to kill her mother.

“You can go one of two ways after that kind of adversity,” Hannah says to me 15 years later. “I could be sitting in the street with a needle in my arm. But there was always someone that helped me through. My grandmother, my aunt, my brother. When I graduated high school, it was the Hendrick Scholarship Foundation (HSF).”

In 2007, Hannah was set to graduate from Plano West Senior High School. She split her time between school and baking cinnamon creme cakes at Corner Bakery Cafe to help her family make ends meet. Her report cards each semester were admirable. But as everyone around her discussed early decision and upcoming campus visits, Hannah didn’t. She had no reason to think about college. She, and two of her older siblings, Bethany and Joshua, lived in a two-bedroom apartment. Her other brother, Ethan had graduated from high school with such a stunning record he got a full ride, but had still been forced to drop out to pay his bills. There was certainly no college fund set aside for Hannah.

“Adversity comes in many forms,” Gregg Pappas, Executive Director of HSF says. “That could mean economic adversity, most of our students fall below the poverty line. For others, it could be their family situations … Some students have medical issues that have held them back. Most students work jobs not only to support themselves, but their families as well. A lot of pressure is placed on them at a very young age to be significant contributors to the family income. Hannah had the grades and the desire, all the things we look for.”

Since its establishment in 1991, HSF has offered $1 million in multi-year scholarships to over 325 students in Plano. One of them was Hannah. Like many Hendrick Scholars, she is the first in her family to graduate college.

Today, Hannah is a sharp 28-year-old single mother to a seven-year-old firecracker named Briah. “She talks a lot and remembers everything. I tell her that’s her best and worst quality. When I told her I was being interviewed she wanted to know if you’d ask what my favorite color was,” she chuckles.

Hannah works in the credit department of a flooring company, calling clients who owe money and seeing to it that it’s returned. Though she once dreamed of being a fashion designer, she enjoys the sense of accomplishment she feels when she collects on a debt that has been stewing, sometimes for years.

“I wasn’t heading in the direction of a degree.” Hannah admits that without HSF, she wouldn’t have gone to college at all. “Whenever the foundation people ask me for help, I’m there.”

Nan

From the time Hannah was three years old, it seemed she was born under an unlucky star. The moment her father killed her mother, her life irrevocably changed for the worst. She was too young to put into words what she’d seen and it was hard to understand the sudden flurry of police and CPS agents swooping in around her and her siblings. All she knew was that her parents were gone, and she and her siblings were moving to Mississippi to live with their grandmother, Ester, who they called Nan.

Nan was a fierce, salt-of-the-earth woman. She wore her hair short and curly, like most elderly Southern women do and had so few vices they could be counted on one hand: Pepsi, cigarettes and Jeopardy. Nan never missed a showing if she could help it and wrote down her score on a pad of paper as she followed along with Alex Trebek. By the time she adopted her four grandchildren, her body was failing her, but she hid her health issues and her grief over her daughter from the children. They had been traumatized enough.

Hannah’s father had been deported to Pakistan, never to return. Nan took on the challenge of holding the rest of the family together.

“We were lost kids and we put her through hell,” Hannah admits. Though they originally lived in an apartment, over the next few years, they moved to a trailer and then to a small house that backed up into the Mississippi woods. Between an ill old woman and four wild children, the house was incurably messy.

Hannah was too embarrassed to invite friends over so as she grew, the woods became her playground. “I’d get lost in them,” she recalls. She and her siblings spent their days running around rural Mississippi, climbing trees and splashing through shaded, muddy creek beds. Half the time, Nan never knew where they were. She was a tough-as-nails, old-school woman who didn’t put up with “crap” but was too infirm to do more than yell for them. She became a common sight in the neighborhood, revving up and down the streets in her gold ‘86 Oldsmobile Cutlass Ciera, blaring her horn and shouting for the miscreants, an open Pepsi can in the cupholder. If none of that worked, when they finally tramped inside for dinner, covered in grass stains, she’d hit them with switches.

“Of course, that never stopped our adventures,” Hannah recalls. “And if you lied to her—oh my gosh.” Once, when Hannah’s older brother went to jail, she showed up to bail him out. Point blank, she told him it was the one and only time she’d bail him out, so he’d better not do it again.

In 2014, Christina Morris disappeared from Plano. Many people wouldn’t rest until she was found.

Nan had next to no money, growing health issues and had lost her daughter. But for six years, she held their family together and in line. Hannah’s maternal grandfather only came to see them once after their mother’s murder. Hannah still wonders why. But Nan fed them, clothed them and took care of them when they were sick. She became the single, sturdy pillar in their dysfunctional lives.

After six years in Mississippi, Hannah’s oldest brother, Joshua, turned 18 and decided to return to Texas. Hannah and Bethany had both joined a local Girl Scouts troop while Ethan, now in high school, had become one of the best students in his class. On the day Joshua said goodbye, Nan looked up at him and frankly declared that he wouldn’t see her again. He waved her off, since he was planning to visit soon for Hannah and Bethany’s birthdays.

Five days later, Nan didn’t arrive to pick the girls up from a troop meeting. Hannah and Bethany waited as all the other girls ran off to their mothers’ and fathers’ cars, one after another, their troop leader checking her watch periodically. They called Nan, but every call went unanswered. Finally, the troop leader offered to drive them home.

Nan’s car sat in the driveway. They tried knocking on the front door and ringing the bell. There was no movement inside the house. So Hannah walked over to her own bedroom window, lifted the panel and hoisted herself inside. It was still and quiet as she wandered from room to room, as if no one was home. She peeked into Nan’s room. Nan was lying on her bed. Hannah tried to shake her, but she wouldn’t wake up.

“When she died it was surreal,” Hannah recalls. “This tough old broad—there’s no way she’d die. There’s no way death got her.”

Joshua was shocked. He begged his roommate to drive him somewhere, anywhere. They drove to a small waterfront in Carrollton. He sat down and stared over the surface, remembering the last words Nan said to him.

Aunt Susan

Hannah, Ethan and Bethany packed up their lives again. This time, it was their Aunt Susan, their uncle and their five children who became their guardians. They left Mississippi, the shabby house and the woods, for a custom-built seven-bedroom ranch house in Auburn, Pennsylvania. It couldn’t have been more different from Nan’s house and Aunt Susan couldn’t have been more different than Nan.

Aunt Susan was what Hannah calls “a true Northerner.” She kept her hair short and prim, dyed ash-blonde to mask the growing gray, and had a softness to her after bearing five children. A stay-at-home-mom, she ran a structured household; not an easy task with five of her own children, two nieces and a nephew. Every night, the family sat down and ate a home-cooked meal together.

Hannah was in awe of the house. Everyone had their own room and got to help design it. Hannah picked mint green walls and a fuschia carpet. They had an expansive property, two acres at the top of a hill, with a basketball court, a treehouse and an above-ground pool. When winter brought heavy snow, they got out sleds and took turns flying down the slope.

But it wasn’t perfect. Hannah readily admits that she and her siblings were second-class citizens in Aunt Susan’s house, “outsiders.” Aunt Susan was stringent and extremely religious, which soon took its toll. Joshua was far away in Texas and not long after the move, her other brother returned to Mississippi because he couldn’t get along with their new family. Aunt Susan, who hadn’t been on good terms with Nan, forbid them to discuss her.

“She’d pour holy water on our heads for it,” Hannah adds. The strict rules and holy water baptisms bothered Bethany and Ethan much more than they bothered Hannah, who liked having other kids around. Besides, Aunt Susan was the one link that remained to their mother and Nan. She carried something of their faces in her face. Hannah was content with that.

After a few years, their aunt and uncle sat Hannah and Bethany down. They announced that they’d spoken to Joshua and he was willing to take over as their legal guardian. Ethan had already left. They suggested it might be better for the two girls to move in with Joshua in Texas.

Joshua

Gone was the huge house and the sledding hill, the large bedroom Hannah designed herself, the regular nightly meals, the religious environment, the holy water and the homeschooling. At 13 and 15 respectively, Hannah and Bethany were dropped off at Joshua’s sparse one-bedroom apartment and sent to public school.

Just remembering it, Hannah laughs and shakes her head, “Talk about shell-shock.” Joshua was just 23 and his life since moving to Texas had been rocky. He didn’t share the same father as Hannah and the rest of their siblings, and without a support system and Nan’s firm hand, he had fallen into the world of drugs and gangs. He had literally no space in his life for his two younger sisters. His lifestyle was alien and, at times, terrifying to them. They moved into a two-bedroom apartment, but it was loud, strangers and drugs passing in and out. Joshua was often out late into the night, sporadically home.

“I don’t know what anyone was thinking, why my aunt and uncle thought that was a good idea,” Hannah admits. “He didn’t have much of anything, but you know what? Joshua wanted to take care of us; he was the only one who wanted us.”

Back in Texas, Hannah and Bethany got in touch with two of their other uncles, brothers of their father who owned a restaurant in town. For the first time in ten years, they connected with their father’s side of the family. Hannah’s feelings about her father were incredibly complicated, shaded with betrayal and terror. Anger was easy to carry. The rest of her emotions were more difficult to admit. Despite the horrific thing he’d done, she spent a long time yearning for the stability and love only a parent can provide, hating the only person in the world who could still offer that.

A couple of years after they had moved back to Texas, Bethany received a Facebook message from a strange woman who introduced herself as their father’s new wife. She had pictures from their childhood and offered to send some to them. Their father had remarried and told his new wife that Hannah’s mother had died in a car accident. Together they had three more children. They lived in Canada. With mixed feelings, Bethany agreed to speak to him on the phone. He asked her why none of his children had ever tried to contact him, saying, “You had each other but I was alone”.

“My anger tortured me,” Hannah says. “He took something away from me that everyone else has, my mother. So many people say that the most important person in their life is their mother. He robbed me of that and then got a second chance at life. My mom didn’t get to raise her kids. I’d hear people talk about their relationships with their moms and I’d never know what that felt like.”

A couple of years later, their uncles reported that their father was dying of cancer. He wanted to speak with them. None of Hannah’s siblings wanted to talk to him. But she, the youngest, the one who’d been witness to his crime, agreed to a Facetime call. She saw a man on his deathbed, thrilled just to talk to her from afar. He said he thought about her all the time.

Hannah trails off. It probably won’t ever be easy for her to talk about her father. Sometimes it’s impossible. “I have so much emotion about him, but I saw a dying man crying because he loved me. He’s dead now. But he was my parent. I got closure from it.”

Hannah

Today, Hannah and her siblings are living good lives. Joshua did some jail time but he found God, turned his life around and now works as a photographer in Pennsylvania. Ethan, who had to give up his full ride to college, has a career in real estate and a nice home in Prosper. He frequently babysits Briah when Hannah is busy. Of all her siblings, Hannah is closest to Bethany, another recipient of a Hendrick Scholarship, who has two kids of her own. They both frequently attend fundraisers and rotary clubs to speak about how HSF helped them.

She worked hard for her degree, taking full advantage of HSF’s academic advisors and volunteer coaches, who came alongside her to offer support and guidance along the way. She graduated with a business degree from Texas Woman’s University in 2016.

“When HSF offered me this scholarship, it was life-changing. I don’t have student loans. I have a degree. It’s opened up so many doors for me,” she says. Hannah is determined to give Briah the kind of childhood she didn’t have. HSF gave her all the tools she needs.

Every year on the anniversary of their mother’s death and again on Nan’s, all four siblings meet at a small lake in Carrollton, known to them as “the spot.” They don’t have graves to visit; Nan’s ashes are in a memorial in Pennsylvania and their mother’s ashes are in Bethany’s closet. So they go to the lake Joshua discovered the day Nan died and together, lay flowers down to honor them.

Hannah has a gift her mother didn’t get: the chance to raise her child and raise her well. “Briah is my heart, my everything. Wanting the best for her makes me do my best. She keeps me on track, focused and grounded.” Hannah pauses, thoughtful. “I understand how my mother must have felt about me, because of how I feel about her.”

Originally published in Plano Profile’s August 2018 True Crime Issue under the title “Lost Girl.”