Postured eagerly at two adjacent grand pianos in a large living room, mother and daughter Donna and Rebecca Glass spent entire Saturdays practicing music as early as Becky’s toddler years.

“I would be at one, and my mom would be at the other,” Becky recalled. “She would play, and then I would play the passage back to her. I’d work on it for about 30 minutes, and then I’d say ‘Mommy! I need more music!’ And she’d have to come play something new.”

Donna remembers these cherished moments with awe. It was never the forcing of a skill on her daughter. It was a passion that overflowed from Becky even at 3 years old.

“Sometimes we would work for eight hours on a Saturday,” Donna said. “Becky was so little, I couldn’t believe she had the stamina.”

Fast forward

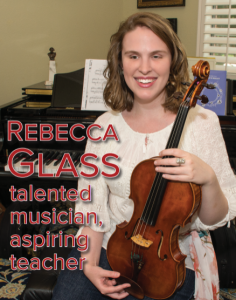

Now a professional violist in her early 20s, Becky, a Plano native, still doesn’t read sheet music. But it’s not for lack of skill or talent. If her extensive list of accolades is not convincing, one might take a few moments to talk to her doctoral advisor and well-known professor Mark Jackobs at the Cleveland Institute of Music (CIM) in Cleveland, Ohio. Set to earn her doctoral degree by age 26, Glass has a whole list of honors to attest to her remarkable gift.

So why doesn’t a professional musician read print music? Becky doesn’t read print music because she can’t. She’s blind.

Extraordinary talent

To most, Becky’s accomplishments are impressive on their own. The fact that she’s blind makes them even more extraordinary.

She’s performed as a soloist with the Fort Worth Symphony, in numerous recitals at CIM, and has worked on chamber music collaborations in a variety of concerts and festivals.

While the natural assumption may be that Becky did not have the “normal” upbringing and experience when it came to her craft, she tends to approach the topic a bit differently.

“I think music and typical experience do not go together for any student because everybody works so differently,” she explained. “It all boils down to the fact that when you, the musician, go on stage, you have a polished and finished product. However, no performer gets to that point exactly the same way.”

Becky admits studying and playing is unique for her, as she learns her pieces by ear. She notes that most people who sight read music still end up memorizing the piece for a performance.

“They have to learn the technique, just as I do. They have to be up on stage, look put together, and play beautifully,” she stressed. “The expectations are the same.”

Glass concedes that while final expectations are the same, her time commitment is larger when initially learning music.

“Most people who are looking at music must play it a while before they memorize it,” Becky said. “For me, I go straight into the memorization process. I’ll spend many hours a day memorizing before I can polish a piece.”

Of course, this process is nothing new. It began when Becky finally surpassed Donna’s ability to play with ease when she was about 8 years old.

An early start

“I officially started taking piano when I was 4,” Becky said.

Donna said their family had looked all over for a teacher, but were consistently told Becky was too young, and her blindness further complicated the search.

“Fortunately, we had gotten a piano that needed tuning at the time, and an Austrian piano tuner came over,” Becky said. “He and my mom were talking, and he said, “I’ll teach her.’”

After eight or nine months of working with the piano tuner she now speaks about quite fondly, Becky was able to get into a piano studio. “It was all because of him saying ‘I’ll take a chance,’” she said.

While she does know Braille music, Becky explains that is something she uses mostly as a reference point. “Now with the amount of material I have to get through, I have two hands going on the piano or two hands on the viola. [Braille music] is going to slow me down,” she explained.

Instead, Becky has her pieces recorded and memorizes them. Barbara Sudweeks, Associate Principal of the Dallas Symphony Orchestra, Southern Methodist University professor, and Becky’s private viola teacher while she was in middle school, Shepton and Plano West, has helped significantly with this process.

“When a recording of a part is made, not only do I have a part to work off of, but the recording also goes into my library,” Becky explained. “Much like one keeps print scores, these recorded parts will always be on hand for me to reference down the road.”

Sudweeks has been doing the majority of Becky’s viola recordings since the two began working together.

“You can imagine all the quartets, symphonies and the main viola solo repertoire that needs to be covered each semester,” Becky said with appreciation.

In addition to music, Becky and Sudweeks share a love of travel. “We’re travel buddies,” Becky said. Sudweeks has joined Becky and the Glass family for journeys ranging from Turkey, to Morocco, Eastern Europe and Israel. “My family likes to travel a lot and that has played a big part in my musical interests,” Becky said, as she explained her dissertation topic which is focused on the role folk music has played in the twentieth century viola solo repertoire.

She recalls her favorite years of high school in Mr. McKinney’s humanities class at Shepton, but said she believes education—life experience—outside of the classroom is crucial to a child’s development as well.

“I was very lucky to have parents who were willing to take me everywhere,” Becky said.

After graduating from Plano West Senior High, Becky began studying at the Cleveland Institute of Music, one of the top music conservatories in the nation, where she earned her bachelor and master degrees.

Cleveland Institute of Music

“Southern girl shock” is how she classifies her reaction to her first winter living in Cleveland, Ohio.

“Most days it was below 10 degrees,” she said.

“We don’t deal with using mobility canes in snow down here, and so all of the sudden I’m up there and the snow is up to my knees and my cane’s getting stuck in the snow!” she laughed. “It can be crazy, but it’s great. After you live there a while you get used to it.”

As for the conservatory, Becky describes it as wonderful. “It’s a very tight community,” Becky said. It’s very welcoming. They’ve been great about getting me music a little early so I can get it recorded, and the theory department has gone out of their way to help in every way possible.”

However, despite her love for the school, Becky loves many places. She feels fortunate she grew up in Plano, where the diversity of the students around her helped her to rarely feel singled out.

She also loved Cairo, Egypt, where the tour guides had no problem lifting her up to touch 5,000-year-old mummies and helping her to climb on ancient ruins.

And she loved Poland. “We were in Malbork, the biggest castle in Europe,” Becky described. “It is Medieval and is in use all the way through today. It’s a huge museum. They’ve brought in or maintained all the wood carvings and tapestries from the original periods. We had a guide who would just walk us through and say ‘She can’t see. I’m just going to let her touch this.’”

“She got to actually touch these 15th century altar pieces and tapestries and everything,” Donna said. “It was so nice!” Becky added, “This type of experience is why traveling is so wonderful for me.”

Despite her taste for exploring the world, Becky said she chose to stay at CIM for her doctorate because of the great bond between her and her renowned teacher, Jackobs, of The Cleveland Orchestra.

Aspiring to one day teach at the college level herself, Becky knows she’ll need to develop a few special pedagogical techniques.

“I need to hear what most teachers are able to see,” Becky said, referring to her identifying a student’s slight slouch from the sounds of their playing. “You have to consider I’m looking into college-level teaching, and so I have to be able to pick up on all the visual cues that any teacher would observe in order to give students good feedback.”

She works on these skills in her lessons with Jackobs. “Especially since I’ve started my doctorate,” she said. “I’ll actually spend time with Mr. Jackobs in lessons, and we’ll talk about ‘So if a student’s playing with a crooked bow, what sounds can you listen for?’ This is going to be my job, so figuring out these strategies is what I will need to be doing and have been working on.”

Much like her mother who responded to her own dedication to helping her daughter succeed with a simple, “You’ve got to do what you got to do,” Becky doesn’t seem to let anything stop her. As for how she got there, Becky stresses hard, consistent work and avoiding comparison.

“Don’t be caught up in what your peers are doing,” she said. “Make sure you’re looking ahead. It’s all about your end goal. You must have mentors you trust and who feel strongly about helping you prepare for the future.”

Photography: Mike Newman