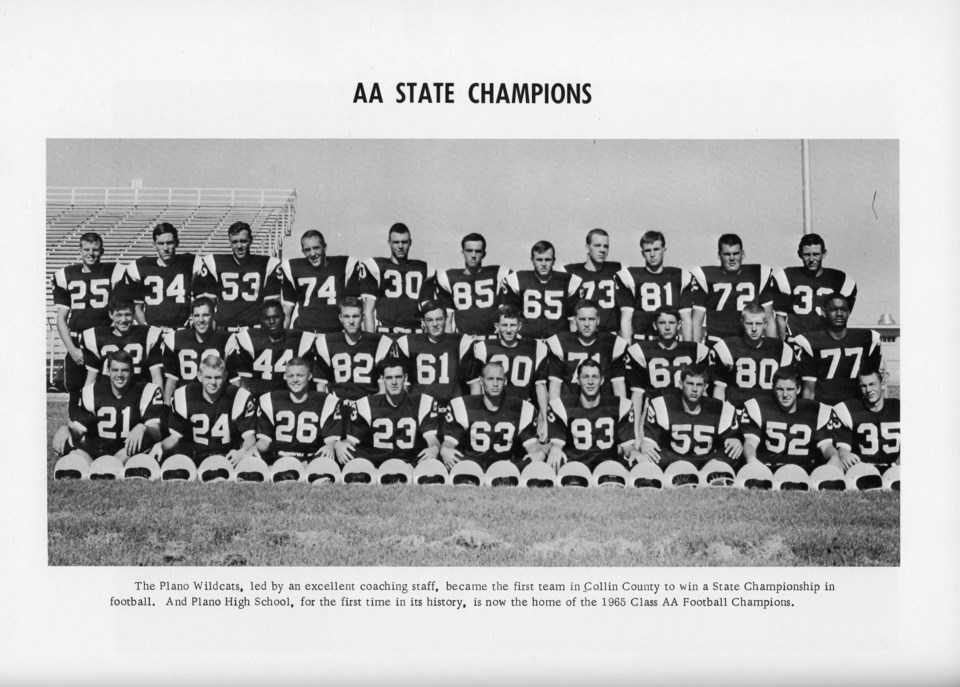

In 1964, Plano schools were integrated. In 1965, the Plano Wildcats claimed their first state championship.

“Back then we were ‘colored'”

Douglass community, one of the oldest neighborhoods in Plano, is little more than a narrow collection of streets where pallet houses sit on cluttered yards. It isn’t unusual to see office chairs wheeled out onto the porches. On one such porch, an elderly woman drinks Pepsi by her front door, watching the cars that occasionally amble by on the quiet streets. The highway and Home Depot form a huge wall on one side of the neighborhood and the other bleeds into downtown Plano.

Today, there is one business in Douglass, a furniture refinisher. But back in the 1920s, up until the 1950s, I Avenue was lined with restaurants and shops. There were candy shops, a barber, a beauty parlor, nightclubs and even a hotel, because that was the only place where Plano’s black residents were allowed to live, work and play. Now, just houses and churches remain.

“We all grew up in that one little neighborhood on the east side of Central Expressway,” Plano-native James Thomas told me recently. He has lived in Plano all his life and played on the Plano Wildcats football team from 1966-70. Today, he serves as the homeless liaison for Plano Independent School District. He pulls out his phone to show me a picture from an old Plano paper of him and a few students from the former Frederick Douglass Elementary, all standing in a neat row. They were being celebrated for perfect attendance.

“Recently I was talking to my son. He used to play football in Plano, too. He told me that after the game, all the kids would meet at Whataburger and talk about the game and hang out, and he asked where the kids hung out when I was playing ball,” he said softly. “And I told him, ‘Nowhere’. Back when I was growing up, we couldn’t go into restaurants because we were African American. He told me, ‘Dad, I’m being serious. You couldn’t go into a restaurant because you were black?’ and I said, ‘Back then, we were colored. That’s what segregation was all about.’”

In the early 1960s, while white students attended Plano High School, all black students, grades first-12th, were taught in a four-room school. Once, when one of the windows broke and prominent Douglass community members went to the school district to ask for it to be fixed, they were told that the white schools needed to be taken care of first.

In 1964, the school board voted to integrate, an effort led by Superintendent Dr. H. Wayne Hendrick. On the first day of school, he dispatched PISD employees into the Douglass community to ask African American students to come to class. Suddenly, students like James were enrolled at Plano High School. By 1968, The Frederick Douglass School for African Americans was closed.

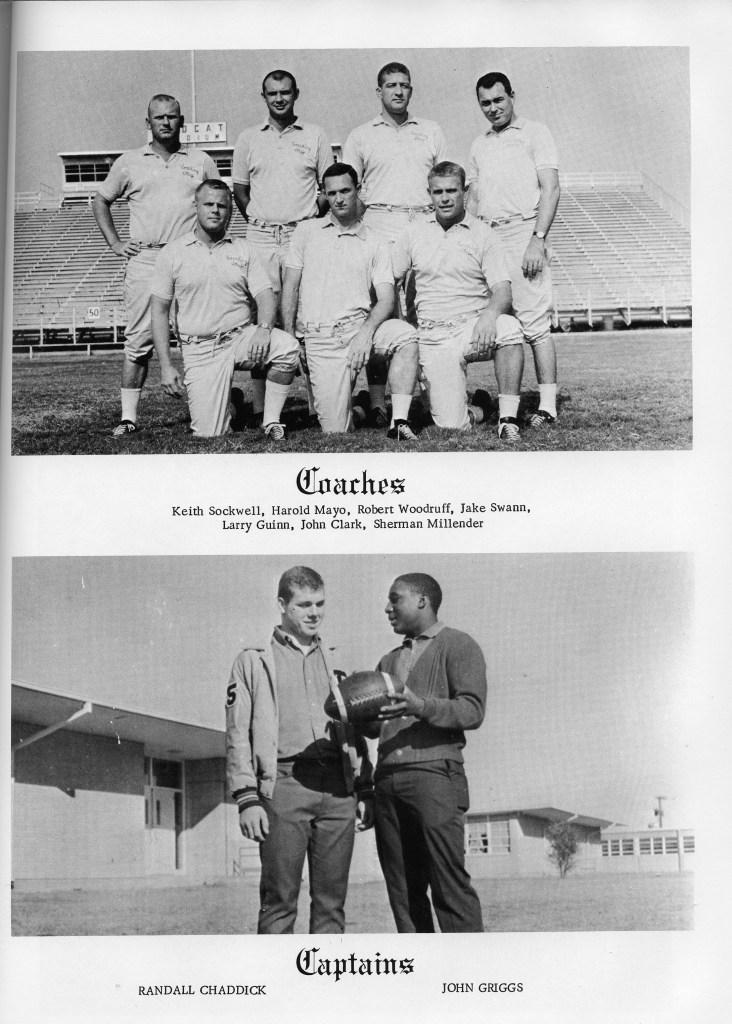

John Clark, Sherman Millender | Captains Randall Chaddick and John Griggs || Courtesy of The Planonian

“We all sat down at the table”

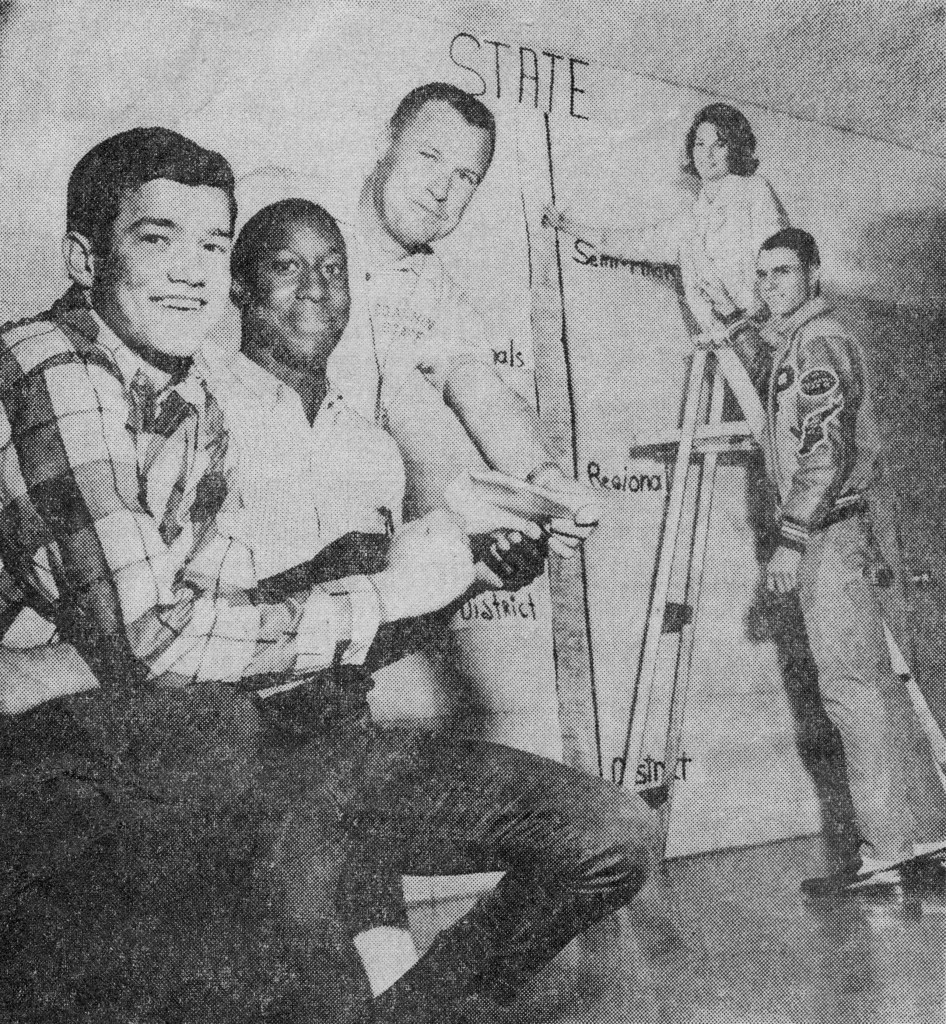

Jeff Campbell, co-director of the Plano Conservancy for Historic Preservation spends his days buried in the archives. There, he came across a note about the Wildcat football team winning their first ever State championship in 1965, just after integrating their schools. An avid football fan, he dug a little deeper, ready to find bloodshed and in 2014, the Conservancy published Football and Integration in Plano, Texas.

“It just struck me. When you hear that there were no problems with integration, you’re initially skeptical. But over and over, we got the same story,” he explains. “Maybe it was because Plano was further from Dallas. You basically had hardworking people who are working to feed their families and maybe that played a big part in it.”

Ken Bangs, who played football before the integration, once told Jeff, “There was a separation [between races]. It would be a lie to say there was not. But there was not a living animosity.”

Even before Plano integrated, the relations between races were, by and large, respectful. It was such a small, personable farm town that everyone couldn’t help but know everyone.

People agree that Plano was different.

All elders, black or white, were respected. One of the most influential figures from the period before integration, in fact, was James (Jim) Thomas I, an African American man who was known as the town’s custodian. More importantly, he was a humanitarian who not only took good care of his own children, but would look after any child, black or white. Thomas Elementary in east Plano was named after him.

Jim Thomas has many descendants, including James and Dollie Thomas, who both work for PISD. Dollie, an HR specialist, is regarded as an expert on Plano history.

“Plano was different,” Dollie asserted in a November speech to this year’s Leadership Plano class, a program run by the Plano Chamber of Commerce. “It wasn’t all good, but it worked until it didn’t work. And when it didn’t work, we didn’t fight. We didn’t fuss. We all sat down at the table. We geared our anger toward progress.”

The harmony Plano enjoyed during this time, constantly shocked Jeff during the writing of his book. In an interview, John Lewis, another former football player told him, “We were in a protected environment. It was not a real world.”

“This was our Camelot,” James said simply.

to right) Kenneth Davis, Rodney Haggard, Ken Bangs and Ronnie Davis

“And we came together”

In the 1960s, every Friday night, Plano shut down for the football. When the Wildcats travelled, the whole town travelled with them. In 1964, Plano had never won a State championship. Then, Coach Tom Gray and assistant coach John Clark were handed Plano’s first integrated football team.

“I can remember the black guys coming in,” Ken Bangs relates in Football and Integration in Plano, Texas. “They didn’t know what to expect, and we didn’t know what to expect. They stood and looked at us, and we stood and looked at them … and we just came together and started talking. … We agreed that we were all pretty much alike. … They were sweating like we were sweating, they were hurting like we were hurting and they were vomiting like we were vomiting. And we came together.”

Coaches Tom Gray and John Clark set the tone. Players remember Coach Gray announcing, “This is happening, and we will be a better team because of it.” He told them that he didn’t expect any problems and proceeded to train them harder than they’d ever been trained.

He told them, “If you will be dumb enough to follow me and do what I tell you, I will make winners out of you.”

By treating all of their athletes the same, brooking no nonsense and training the team to exhaustion, the coaches taught them to rely on each other. Soon, Plano, a 2A team, was playing 3A teams and winning.

There were pockets of resistance. At some away games, the team was booed. So the players united and held each other accountable. They refused to let each other quit when tensions got high, telling each other that they’d never had a Douglass community player quit.

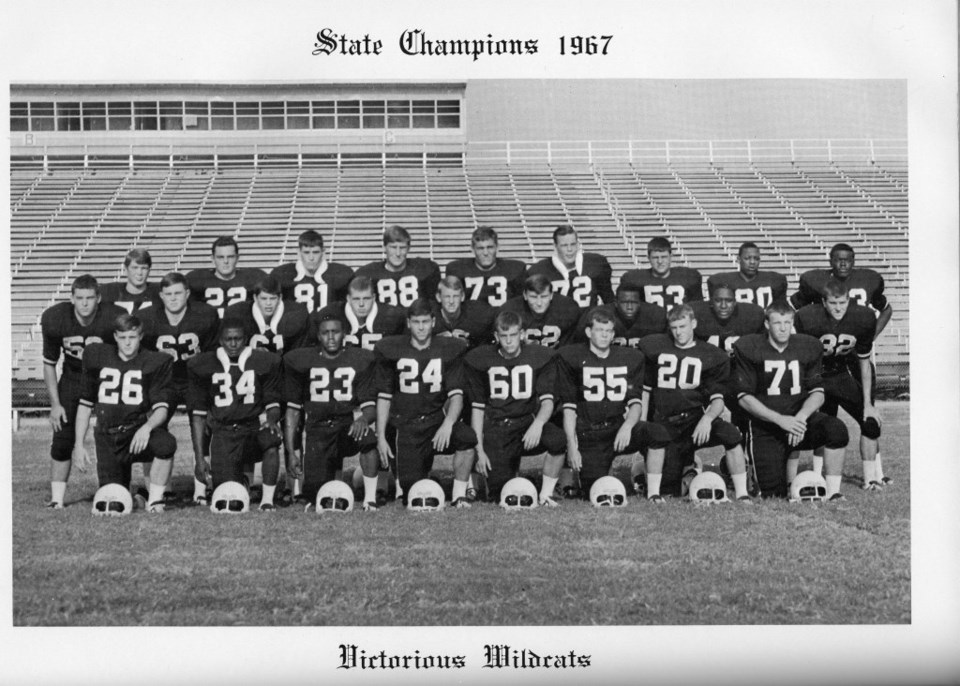

December 18, 1965, the Plano Wildcats claimed their first State championship. Plano has gone on to win seven State championships total. After that first historic win, Coach Gray left Plano and Coach Clark took over, continuing the legacy of excellence in Plano football that still exists today.

Read more- House of Champions: World Olympic Gymnastics Academy

Players like Kenneth Davis, Johnny Griggs and Alex Williams were instrumental during these years. Kenneth David was a superstar offensive tackle who went on to play for the University of Oklahoma. Johnny Griggs was the Wildcat’s All-state running back and he was so good, he became a team captain alongside Randall Chaddick. Alex Williams made history as the first black quarterback to play for Plano High School.

James Thomas began playing for the Wildcats in 1966. Alex Williams is his cousin and he remembers that while earlier black players were accepted, people had a hard time cheering for a black quarterback.

“A black quarterback was unheard of on a white team,” James confirms. “Clark got phone calls about it, maybe threats too. The community didn’t want Alex, but Clark put him in and he performed exceptionally.”

Then, in one game, Alex was injured, so the other quarterback, a white student, played the first half. He was noticeably less effective. When Alex came out of the locker room to lead the team in the second half, the entire stands clapped for him.

“That’s when we realized that attitudes had changed,” James recalls.

All of the coaches Clark hired upheld his ideals. For example, one assistant coach, Jack Swan, introduced himself to James by announcing he was going to be a linebacker under his guidance.

“‘Hey,’ he said. ‘From now on you’re in my group. When I say run into that wall, you’ll run into that wall 100 percent of the time. You understand me?’” James laughs. “I said, ‘Yes, sir,’ and as he walked away, I thought to myself, ‘This white man is crazy.’ But the funny part is, by the time I graduated I’d have run into twenty walls for that man. He’d have run into 40 walls for me.”

The better the team did, the more accepting the community became. Acceptance spread from the school in a ripple effect. A human relations committee formed in response, so that any issues could be discussed before they became volatile.

“The human relations committee generated conversation,” Dollie Thomas said. “These weren’t just business people and they weren’t just white people. Every section of the community came in and talked about goals for Plano. Even during integration, while Dallas was on fire, Plano had the smoothest integration process.”

Overall, Coach Clark left Plano with a stunning record of 107-17.

“We built that tradition”

Not every Plano football player has gone on to greatness. In fact, most of them haven’t. Over the years, friends have asked James Thomas how Plano beat so many teams, made up of bigger, stronger, objectively better players. He attributes it all to the attitude Coaches Gray and Clark created.

“We played as a family,” James explains. “I can’t get you by myself, but my best friend who’s playing right beside me could. As a team, you couldn’t beat us. Right now, Plano has this tradition of excellence that players are growing up with. Well, we built that tradition.”

Read more: Full STEAM Ahead at Plano Academy High School

Pat Thomas, James’ little brother, played professional football for the Los Angeles Rams. He went all the way to Super Bowl XIV.

As part of the nationwide Super Bowl 50 celebration, the NFL started the Super Bowl High School Honor Roll program, acknowledging schools and communities that have directly influenced Super Bowl history with Wilson Golden Footballs. A couple of years ago, Pat Thomas was honored with a golden football, which he gave to Plano Senior High School.

Before the 1979 Super Bowl, a sportscaster came up to Pat and asked how it felt to be on the verge of the biggest game of his life.

James remembers his brother’s answer fondly. “He said, ‘Well, no, this isn’t the biggest game of my life.’”

The sportscaster reasoned that no game could possibly be bigger than the Super Bowl and Pat replied, “I played for Plano High School. I played for state. That’s the biggest game of my life.” He explained that in the Super Bowl, he was playing with a group of adults and friends and getting paid to do it. But when he played for state in Plano, he wasn’t paid a dime and he wasn’t playing with his friends.

“Everybody on that team, black or white, was my family,” Pat Thomas said. “Our coaches were our fathers. We believed in them and trusted them. I played with my family. There is never a game that will be bigger or higher than that.”

Originally published in Plano Profile’s January 2018 issue under the title “This was our Camelot”