More than 160 years ago, France was recognized around the world as the pinnacle of winemaking, just as it is today. Celebrated regions like Bordeaux, Burgundy, Cognac, the Rhône Valley and Champagne were prized by royalty and connoisseurs for their sublime, age-worthy wines. The catalyst for this flavor success was Vitis vinifera, the European grape species that produces the world’s great wines fermented from chardonnay, pinot noir, cabernet sauvignon, syrah and marsanne.

But by the 1870s, Europe’s wine industry teetered on the precipice of extinction. That’s because decades earlier, European botanists and viticulturists had begun importing American grapevines and rootstocks to study their resistance to the fungal diseases afflicting the continent’s vineyards. Little did they know that hitching a ride in this imported plant material was a scourge known as phylloxera. Native to North America, phylloxera is a tiny yellow vampiric louse that sucks the sap from vine roots and injects saliva that is toxic to the plant. Its pernicious bite precipitates a long, slow death. The louse began feasting on the European continent’s millions of vulnerable vinifera vines. The infestation first emerged in 1863 in France’s Rhône Valley and western Languedoc regions. The contagion spread rapidly, traveling from plant to plant by wind, farming tools and clothing. Welcome to wine hell.

The Cognac region of France was devastated, losing up to 90 percent of its vineyards, sending the area’s economy into a tailspin. In Bordeaux, Baron James Mayer de Rothschild’s Château Lafite — one of the world’s most famous and prestigious wine estates — was nearly ruined. Over the next few years, phylloxera attacked vineyards all over Italy, Switzerland, Germany, Spain and Portugal. By the late 1890s, up to 90 percent of Europe’s vineyards were withered and dying. Even vineyards in Australia, New Zealand and South Africa were stricken. Wine quality plummeted as winemakers began blending, diluting and adulterating dwindling supplies to meet demand. The French wine industry was in full-blown crisis as international wine buyers retreated from its markets. Winegrowers fought back by flooding their vineyards to drown the louse, burying live toads near the roots of their vines to draw out the toxins, and using chemicals like human urine and carbon disulfide as repellents. Nothing worked.

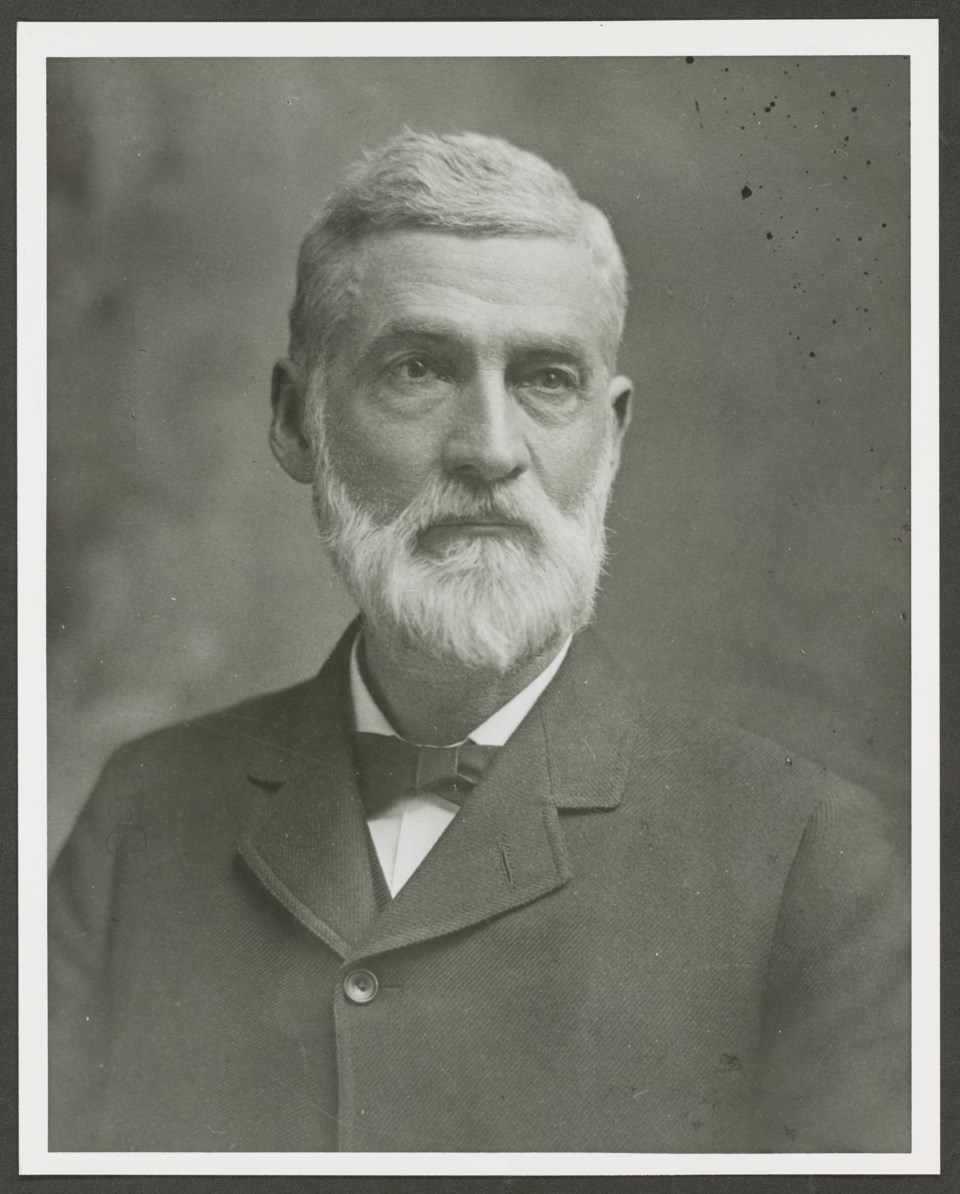

In 1874, the French government responded to this catastrophe by offering a reward of 300,000 francs — the rough equivalent of $1.5 million in current U.S. dollars — to anyone who could develop a cure for the phylloxera plague. The prize was never awarded, as no one found an actual curative. But that doesn’t mean a solution wasn’t discovered. The remedy emerged in the unlikeliest place: the nursery of Thomas Volney “T.V.” Munson in Denison, Texas. A brilliant 19th-century viticulturist, Munson obsessively studied and bred native American grape species on his Denison estate. His extensive research and breeding experiments revealed that the rootstocks of grape varieties native to Texas were resistant to phylloxera. Not only that, but they thrived in the chalky, marly soils found in the afflicted areas of France.

Munson shipped thousands of phylloxera-resistant Texas rootstocks to France and beyond, where they were grafted onto European vinifera vines. His discovery saved the French wine industry and rescued vineyards worldwide.

Fast-forward to today: Munson’s rootstocks and grape varieties are being used as seed corn for modern, innovative breeding programs, like one launched at Texas A&M this year. “It’s an odd little story,” says Patrick Whitehead, the winemaker at Blue Ostrich Winery and Vineyard in Saint Jo, Texas. “I’ve always said it would make a cool little movie. But people just don’t know it.”

***

Just outside of downtown Denison, at the intersection of Hanna Street and Mirick Avenue, stands Vinita, Munson’s circa-1887 two-story brick home, crowned with a dormered attic. Designated a Texas Historic Landmark in 1967, Vinita has Italianate-style features, including overhanging eaves with brackets and tall slender windows accenting long covered porches on its northern and eastern sides. It’s a homestead that drips historical novel romance.

Catch the sunlight at just the right angle through a window near the kitchen, and you can see the name “Viala” scratched into the pane in elegant cursive. Born in 1888, daughter Viala was the youngest of Munson’s seven children. She was named in honor of French viticulturist Pierre Viala, who helped Munson exorcise the world’s wine grape demons.

The home once towered over a 350-acre expanse of farmland, but today, it is encircled by the encroachment of modest residential homes. When Denison’s Grayson College acquired the estate in the 1990s, the walls were stripped down to the lath, the thin flat strips of wood nailed to the studs that form the foundation for plasterwork. This work exposed scraps of the home’s original wallpaper. From these remnants, pattern designers were able to recreate the wallpaper used to restore Vinita to its original splendor.

Born in Astoria, Illinois, in 1843, Munson graduated from the University of Kentucky in 1870, where he studied botany and horticulture. Not long after completing his education, he married Ellen Scott “Nellie” Bell, and in 1873, the couple moved to Lincoln, Nebraska — land of corn, wheat, and cattle. There, Munson worked as a nurseryman and began experimenting with grape cultivation, developing new grape varieties through cross-pollination and hybridization. Munson was prescient in his quest: by 1877, the Cornhusker State was harvesting 260,000 pounds of grapes annually, fueling its nascent and tiny wine industry.

But Munson’s experiments failed due to the harsh climate and a near-biblical plague of grasshoppers so thick that the trains were halted to avoid derailment when the rails became slick with hopper carcasses. In 1876, distraught over his challenges in Nebraska, Munson moved to Denison, where two of his brothers lived. He discovered a rich diversity of soils and native grape species he had never seen before. He was stoked.

“I had found my grape paradise!” he wrote in his 1909 book, Foundations of American Grape Culture. “Surely now, thought I, ‘this is the place for experimentation with grapes!’”

For the next few years, Munson continued his research on native American grape species in a crusade to identify vines that could thrive in harsh conditions. That’s a good thing, because outside of California and Oregon, the U.S. is an inhospitable host for the European Vitus vinifera. Texas is particularly brutal on this accelerant of wine snobbery. The chaotic Texas climate, with its extreme temperature swings, droughts, intense sun, dicey soils and hail bombardments, wreaks havoc on vineyards.

***

“If Mother Nature really wants to take your grapes, she’ll take your grapes,” says Grayson College viticulture professor Mark Schabel. “With hail or winds, it’s a kind of roll the dice.”

This region is particularly susceptible to grape-growing mayhem. “North Texas is a big challenge because of the hot and the cold,” says Andrej Svyantek, who heads Texas A&M’s new grape breeding program. “The fluxes come in January and February and even early March. You can get an 80-degree day after a 14-degree day. That’s a lot of stress on grapevines.”

Adding to this meteorological chaos is the myriad of pests that thrive in the Texas climate. There’s the dreaded glassy-winged sharpshooter, a leafhopper that feeds on grapevine stems and leaves. This bug infects the plant with a bacterium that blocks the flow of water and nutrients, an ailment known as Pierce’s disease. Additionally, there are fungal blights to fight, like powdery mildew, downy mildew and black rot, as well as the usurper of wine royalty, phylloxera.

That’s not to say that grapes don’t thrive in Texas. Native wild varieties such as Vitis mustangensis (mustang), Vitis berlandieri (fall grape) and Vitis cinerea (possum grape) have spread like wildfire across the state’s diverse topography. Plus, these wild vines are often immune to such ruinous afflictions.

The problem is that these grapes often produce wines with “foxy” flavors and aromas, a musky essence reminiscent of an overripe grape or a wet dog — Night Train and Mad Dog 20/20 territory. But by implementing Munson strategies like crossbreeding and grafting Vitis vinifera to disease-resistant rootstocks, you can create a resilient homegrown wine aristocracy.

“We have been on pause for more than a century in Texas,” adds Svyantek. “Nobody has continued to do what Munson was doing … until now. We’ve been missing out on over a century of progress in improved flavor, disease resistance and frost avoidance. This is the start of many new things to come.”

Yet Munson’s groundbreaking work went beyond grape propagation; in fact, he was somewhat of a Renaissance man. He was an accomplished artist, filling books with sketches of plants and animals that caught his eye. He was also a prolific inventor, devising machines such as a “lightning weeder and cultivator,” a “rotary dasher churn,” and a “force pump” for use in wells and cisterns.

“T.V. Munson was like [Leonardo da Vinci] in a way,” says Randy Truxal, executive director of the Grayson College Foundation, pointing to a 1911 glass-covered schematic displayed in a cabinet at Vinita. “He created this drawing of a non-fixed-wing flying machine.”

The blueprint depicts a “safety flying car” with three rotors, foreshadowing the modern helicopter. The “da Vinci of Denison” was in the process of submitting his rotorcraft design to the U.S. Patent Office when he died of pneumonia in 1913.

But his work classifying native American grape species and developing hybrid rootstocks etched his name into a nearly forgotten history, even as Munson achieved rock star status in European winemaking enclaves. To commemorate his legacy, the French government awarded Munson the Chevalier du Mérite Agricole in the Legion of Honor in 1888. In 1992, Denison, Texas, and Cognac, France, officially became sister cities, honoring the collaboration between Munson and Cognac native Pierre Viala. In 2002, the French unveiled a statue of Munson in the central square of Cognac.

In the years following his death, much of Munson’s acclaimed research was nearly expunged from the record, succumbing to a deadly pincer of prohibition and neglect. After the passage of the Volstead Act, which enforced prohibition, Texas grape growing and the cultivation of Munson varieties — most of which have been lost — nearly ground to a halt. His daughter-in-law, Minnie, sold his French Legion of Honor medal to a Denison scrap dealer during the Great Depression. One of his medals was intermittently used as a hickory nutcracker and a doorstop. Several truckloads of material from the old Munson Nursery office, including a draft manuscript of Munson’s book Native Grapes of North America, were burned as trash when the building was sold in 1938 and converted to apartments.

“T.V. Munson is one of the most revered viticulturists and plant breeders still to this day, says Michael Cook, a North Texas viticulture specialist with Texas A&M University. “However, unfortunately, he is more well-known in Europe today than he is at his own home in the United States. What’s interesting is, we’re essentially having a Munson revival.”

Head west on Grayson Drive in Denison, and you’ll run head-on into an F-86 Sabrejet. It’s an imposing display in the median just after the road splits off near the entrance to the North Texas Regional Airport. The jet is mounted tilting upward on a massive pipe thrust into its exhaust nozzle, as if it’s poised to drop ordinance on approaching traffic.

Entering service in 1949, the Sabre was the first swept-wing fighter in the U.S. Air Force that could successfully dogfight the deadly swept-wing Soviet MiG-15 during the Korean War. The airport was built on the site of the Perrin Air Force Base, a training airfield for World War II pilots and a key air defense facility until it closed in 1971. To the left of that Sabrejet is the Thomas Volney “T.V.” Munson Memorial Vineyard on the West Campus Extension of Grayson College.

Established in 1974, the vineyard serves as a repository that preserves a fraction of the more than 300 grape varieties bred by Munson in the late 19th and early 20th centuries.

“They’re hybrids of varieties he found locally around Texas,” says Schabel as he opens the iron gate to the vineyard. “He traveled around Texas by horseback and found wild varieties and propagated them.”

The legacy of T.V. Munson is weirdly intertwined with flying machines. Before becoming a viticulture professor at Grayson College, Schabel, a veteran of the California wine industry, was the winemaker at Denison’s Hidden Hangar Winery and Ranch. The expanse that Hidden Hangar occupies was once Gray Field, a municipal airport that operated from 1928 until the 1950s. It served as a stopover for planes traveling between Dallas and Oklahoma City and as a hub for daring barnstorming pilots who used its rolling grassy knolls as launch pads into the clouds.

The vineyard, which serves as a resource for Grayson’s viticulture and enology program, nurtures Munson varieties such as Wine King, Valhallah, Fern Munson (named after Munson’s daughter) and Ellen Scott (named after Munson’s wife). The college receives requests from all over the world for cuttings of Munson vines for research.

Though a community college, Grayson was a pioneer in viticulture and enology studies and certifications in Texas, with its roots reaching back to 1974. Texas universities followed in its wake, with Texas Tech launching a viticulture and enology program in 2009, and Texas A&M breaking ground on a similar program in 2017, although A&M has offered viticulture studies since the early 2000s.

“Back when Grayson College started, nobody really believed that Texas wine could be a big industry,” says Chris Hornbaker, winemaker at Eden Hill Vineyard and Winery in Celina. “And so, the funding wasn’t there for a four-year degree program at a big university like Tech.”

Like Hornbaker, who had a successful career in internet marketing before the grape smote him, many Grayson students had long been steeped in professions such as engineering, consulting and law. Grayson offered these professionals remote study programs so that they could dip their toes into winemaking before shifting careers. Additionally, until recently, Texas law forbade young, underage viticulture and enology students in four-year degree programs from tasting the fruits of their winemaking experiments.

“It’s kind of funny, though,” adds Hornbaker. “[Today] there has to be a police officer on site as the students are tasting the wine to make sure they spit it out.”

Once planted with some 65 Munson varieties, today, Grayson’s Munson memorial vineyard has grown scraggly with age, nurturing little more than 30 specimens. The school aims to replant and restore the vineyard to preserve the 60 to 65 Munson varieties still in existence for propagation and study.

After over a century, Munson hybrids are poised to ignite a new era in winemaking in Texas and beyond. Utilizing modern technologies like DNA fingerprinting, genome sequencing and genetic screening, researchers and breeders who rely on Munson’s genetic material can more easily select for flavor, heat tolerance and resistance to frost, pests and drought. This mission is at the core of the new grape breeding program launched at Texas A&M last January.

“There hasn’t been a grape breeding program in Texas since Munson,” says Justin Scheiner, a viticultural specialist in A&M’s department of horticulture sciences. “It’s a rare thing. Vitis vinifera is not adapted to grow well here without technology to overcome its challenges.”

Using these innovative tools, breeders can dramatically accelerate the selection process for grape characteristics suited to the Texas climate. Rather than planting tens of thousands of seedlings and hoping that, in five years, they will have successfully crossbred for sought-after traits, researchers can genetically screen seedlings and eliminate all but the ones they desire. But grape growers are deploying other technologies as well.

“There are some fantastic things that are going to be happening in the grape-growing world,” says Hornbaker. “Now, we have AI that we can use in the vineyard. The AI can predict when you’re going to get a mold or freeze event and send warnings to your cell phone.”

These advances and the promise of A&M’s breeding program have winemakers like Hornbaker excited about the future of wine in North Texas. He’s planting his vineyards with new organically bred grape varieties, like cabernet volo, a red hybrid grape resistant to mildew and frost down to minus 11 degrees. He plans to use these hybrids to craft unique roses, which he is convinced will be the next big thing in Texas winemaking.

Hornbaker is also encouraging his fellow winemakers and growers to continue experimenting, planting and trying new things. “I’ve proven that you can grow beautiful wines in North Texas,” he insists.

Today, most of the world’s vineyards are grafted onto American rootstocks, nearly all of which descend from species Munson collected, studied, bred and recommended.

Cook says Munson has become a relic of the past since his death. But due to the integration of Munson genetics with new technology, his dusty and discarded star is beginning to brighten.

“It will shine like a spotlight within the next 10 years,” Cook predicts.

And once again, the da Vinci of Denison will rescue and elevate wine from the harsh ravages of Mother Nature. But this time, he’ll do it right here in North Texas. And beyond.

This article originally appeared in Local Profile magazine. Check out the issue here.

____

Hungry for more? Check out our dining guide.

Don't miss anything Local. Sign up for our free newsletter.