Ask what's celebrated on May 5th, you'll probably get Mexico's Independence, that in reality is celebrated on September 16. But Cinco de Mayo, which remembers the Battle of Puebla, is a festivity much more related to U.S. history than you might think.

In 2022, the Library of Congress acquired a batch of some 36 letters from Mexican historical figures that provide a detailed account of the final months of the Second French Intervention in Mexico. Filled with descriptions of complex military planning, weapon inventory and movement, and even tips on how to deal with deserters, the letters covered not only the Battle of Puebla in 1862 but also the intricate interplay of global powers vying for control in the Americas, set against the backdrop of the U.S. Civil War.

In 1861, after decades of internal conflict, the Mexican government found itself bankrupt and unable to pay its debt to its European creditors. While Spain and the United Kingdom sent forces to collect on Mexico's debt, France's Emperor Napoleon III saw an opportunity to take Mexico and turn it into a French colony.

To Napoleon III's delight, things weren't much better for Americans at the northern border. In April, the Civil War broke out with the Battle of Fort Sumter, consuming all the attention, energy and resources of Abraham Lincoln’s government and the American people. If Napoleon III managed to install a puppet government in Mexico, France would be able to trade guns to the Confederacy in exchange for cotton, a scarce commodity in Europe since the Union's shipping blockades.

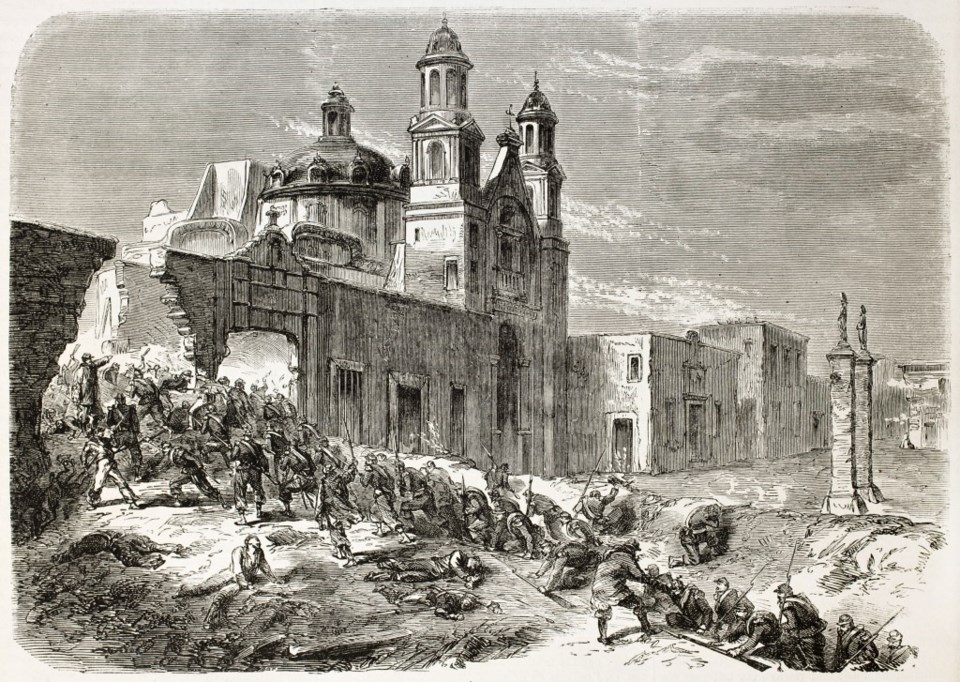

So, confident in its army's supremacy, in 1862, France sent elite forces marching from Veracruz to the capital with the intention of capturing it. But there's a thin line between confidence and arrogance, and the French found out they had crossed it when they came across the heavily fortified city of Puebla. There, Mexican General and Texas native Ignacio Zaragoza led a ragtag army of volunteers that beat the French invaders. It was the first large-scale battle the French army had lost in five decades and it took a full year for France to try its trick again. But by 1863, with Union victories signaling the end of the Confederacy, Napoleon III's plans were frustrated.

While the victory at Puebla only postponed the eventual triumph of the French government, which lasted until its overthrow in 1867, it was a welcomed boost of morale for a struggling nation.

France's defeat in Puebla was critical, especially as Mexico worried that if the Confederacy won, an independent South could carry the threat of slavery to their country, where slavery had been abolished since 1829.

“In 1862, things weren’t going well for the Union in the Civil War, but here in Puebla was a clear-cut victory that completely threw the French timetable off,” David Hayes-Bautista, director of the Center for the Study of Latino Health and Culture at the UCLA School of Medicine, told History. “The news reports just electrified Latinos and jolted them to a whole new level of organization and activity.”

Both the Union's and the Mexican conflict with France's causes were so intertwined for Mexican-Americans who adamantly opposed the Confederacy, that some of the first Cinco de Mayo parades featured flags and Union uniforms and songs both in English and Spanish.

The story of camaraderie between the two nations was not lost on the American government either. According to historian Michael Hogan, during the civil war, Matías Romero, a young diplomat, established a personal relationship with the Lincolns and several Union generals. With these important friendships, Romero managed to secure American aid, despite the official policy.

In 1865, once the Civil War was over, America began taking a more active role in aiding Mexico’s fight against France. General Ulysses Grant, one of Romero’s treasured allies, dispatched 50,000 soldiers to the Texas border, led by General Sheridan, with secret orders to strategically "lose" 30,000 rifles, which would later be "found" by the Mexican troops.

Since the battle, the festivity has become a celebration of Mexican heritage in America, being celebrated non-stop since 1862 in some states like California.

So this Friday, as you sip on your ice-cold Margarita, raise a glass for all the brave volunteers who, by fighting for their sovereignty, unknowingly helped shape our history and brought our neighboring countries a little closer. Feliz Cinco de Mayo!