As COVID-19 spread to Texas last spring and we were all asked to follow "stay-at-home" guidelines, I thought about other times in my life when I was isolated, by geography or living conditions, especially during the mid-1990s when I lived in Siberia. Now that this pandemic has lasted longer than many people expected, I've been forced to reflect again on how past experiences are helping me cope with present challenges.

Back in April when I saw people here in Texas pushing shopping carts out of Walmart and Costco filled with enough food and paper products for a month, I remembered how hard it was to stock up on anything in Russia. Bags of oranges? Flats of peanut butter? Cases of beer? Shopping carts? None of those were part of my life in Siberia.

After living in Russia, I chuckled at Americans last spring who were upset that their favorite fast-food restaurant was shut down, or complained when a store was out of their preferred brand of breakfast cereal. But now I feel the pain, too. I lost some of the contract jobs I was counting on this year. All my overseas travel plans were canceled. Neighbors have been laid off their jobs. Although my husband, Tom, is retired from teaching at Collin College, his colleagues there have had to learn how to teach their courses on Zoom. And by now—given the "six degrees of separation" between any of us—most of us know at least one other person who has contracted this terrible virus.

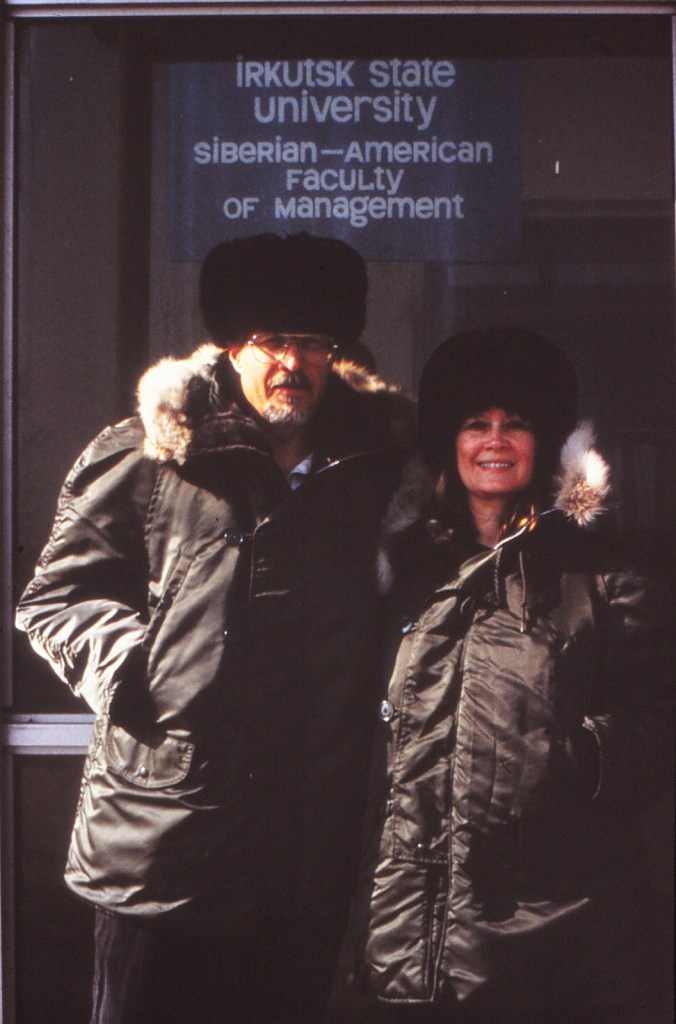

In many ways, my earlier experiences in Siberia have helped me cope with Pandemic 2020. Our Siberian adventure began in 1993, eighteen months after the collapse of the Soviet Union, when Tom and I were hired as professors for a new American university program there. We arrived just in time for an economic depression much worse than this year's recession in the U.S.. Millions of Russians were losing their jobs. Others were still working but not getting paid until months later. Hyperinflation was devaluing the currency daily (sometimes hourly), and prices kept rising rapidly. By the autumn of 1994, the value of the Russian ruble had declined so much that people were paying for food with stacks of banded bank notes of 10 thousand, 20 thousand, and 50 thousand rubles each. (Ten thousand rubles were the equivalent of two U. S. dollars by that time.) Tom and I would fill our shopping bags with stacks of thousands of rubles just to buy a loaf of bread and six bottles of beer at an open-air market.

We lived in two major cities, Irkutsk and Vladivostok, both with populations the same as Fort Worth. Our apartments were in huge, prefab-concrete, high-rise blocks, each building housing hundreds of people. Typical of apartments throughout Russia, ranged in size from 500 to 700 square feet. Each also had a little balcony where we stored extra food—our equivalent of a Texan's beer fridge or freezer in the garage—but ours was open to the air and refrigerated by nature for most of the year.

None of the stores sold kitchen supplies such as plastic wrap, waxed paper, aluminum foil, paper towels, or plastic bags. Instead we used old student papers (homework assignments and exams) for paper towels in the kitchen. We saved all the thin aluminum foil from inside the wrappers of imported German chocolate bars, which we carefully washed, dried, smoothed flat, and pieced together to make larger sheets of foil for wrapping leftover foods.

But the most frustrating aspect of daily life was the lack of dependable public utilities, all of which were all provided by the local governments. Residents had no control over those centralized utilities. All we could do was turn on the light switch, the water faucet, or the radiator and hope that any of them were functioning that day. Life was especially hard whenever the electricity, heating, and water all happened to be cut off at the same time during the Siberian winter.

Water was a precious resource that had to be processed, saved, and rationed. The water that flowed through our taps in ranged in color from clear to amber to orange to purple to black. Cholera bacteria were found in the water supply in Vladivostok, and high levels of industrial and organic pollutants were measured in the tap water of both cities. All of our water for drinking, cooking, and tooth brushing had to be boiled (when the electricity was working), cooled overnight, pumped through a water filter every morning, and stored in recycled plastic bottles before using. We also kept large buckets of water in reserve, in our kitchen, bathroom, and hall, for basic necessities like dishwashing, toilet flushing, and hand washing.

When the pandemic hit last spring, I was especially amused at stories about Americans hoarding toilet paper. In Siberia there wasn't enough toilet paper to hoard. When I recall how much time we spent every day trying to find just one or two rolls of Russian rough, gray toilet paper, I don't know how we got anything else done. At one of the universities where we taught, there was no toilet paper at all; instead, old Marxist-Leninist textbooks were "repurposed" in the toilets, one book per stall. You just tore off the pages you needed to finish your business there.

We took a positive approach toward all those challenges, viewing our time in Russia as an adventure and a chance to watch history in the making. Fortunately we didn't have to deal with a global pandemic, too. But the stark differences between our life there and the way most people lived in the West led me to write a memoir about our experiences, The Other Side of Russia: A Slice of Life in Siberia and the Russian Far East (Texas A & M University Press, 2003). Coping with those long-ago challenges turned out to be good training for what we’re going through now.

Today we're all experiencing an adventure in adversity, stuck at home by necessity, not choice. Many of us are confined to a limited space along with bored kids, cranky spouses, and noisy pets. But my spirits are buoyed by all the stories of young couples learning to cook together, families eating meals together, and distant socializing during this time of social distancing, from "happy hours" with friends on FaceTime, to weddings and graduations "attended" on Zoom. This pandemic has brought out hidden reserves of resilience in many of us, just as Siberia did for my husband and me, leading us to come up with creative solutions to unexpected problems.