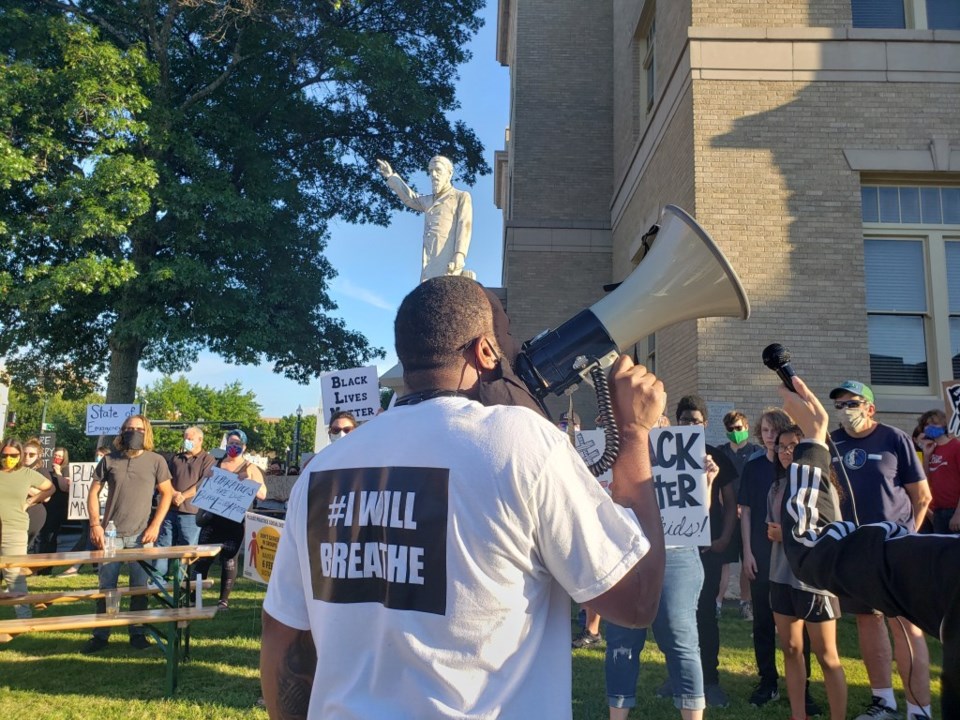

On a hot day in May, about 100 protesters gathered at the downtown McKinney courthouse. McKinney City Council member La’Shadion Shemwell, with Black Lives Matter on the back of his shirt, paced in front of the crowd in front, calling for justice and an end to systematic racism in the name of George Floyd. Above it all stood the statue of the 12th Governor of Texas, James W. Throckmorton, a Confederate general who hailed from McKinney.

“With 200 pounds on [Floyd’s] back, he was uncomfortable,” Shemwell shouted. “This may be uncomfortable for you today, but it was more uncomfortable for him. He is forever silent.”

That day, the statue was simply a part of the landscape but not an unfamiliar part. Throckmorton's name appears all over the Collin County area. In Anna, there is a Throckmorton cemetery. A downtown McKinney street bears his name. His portrait even hangs in Rye, a modern small plates restaurant that is located where his law office used to be. He frowns down at diners eating Japanese elotes and pork medallions.

Now, two months later, citizens are asking city council to remove his statue from the courthouse lawn. More than a 1,000 people have signed a petition for its removal on Change.org:

“James W. Throckmorton was not the worst confederate to come out of Texas, but he was a poltroon. He was given many opportunities to fight with the Union for the freedom of all men, but he was only looking out for himself. We, as McKinney citizens, will not have our city defined by a coward who was ultimately removed from office because of his racist policies. Please stand with us to ensure that this statue is removed and we send a message to future generations that we recognize and condemn the atrocious past of the confederates."

The murders of George Floyd, Breonna Taylor, and many other Black Americans have reignited efforts across the U.S. to remove Confederate monuments and statues. People are hungry for concrete signs of social change, and removing monuments commissioned by the Daughters of the Confederacy and statues of famous Confederates like Robert E. Lee is meaningful work.

However, before it became a controversy, if one searched Google for Confederate statues in Texas, Throckmorton’s did not show up. Only one statue in Collin County was flagged, a small Confederate soldier monument in a graveyard in Farmersville that was donated by the Daughters of the Confederacy. Throckmorton’s slipped by unnoticed because it did not have an attachment to the Daughters of the Confederacy—unlike the recently removed monument in Denton which was embellished with a pair of “whites only” drinking fountains.

According to the Denton Record Chronicle, the statue was taken down in the early hours of the morning without an announcement or fanfare because of public safety concerns.

Frozen in marble, Throckmorton stands guard in the courthouse's shadow, with one arm flung up, finger pointing to the sky. Local legend claims that his finger has been stolen before by mischievous teens and has had to be replaced. His plaque reads: “A Tennessean by birth, a Texan by adoption. A slight tribute to the patriot and statesman, from his fellow citizens and admirers, because of his pre-eminent personal worth, and distinguished public service.”

Before he became governor, Throckmorton was well known in McKinney, according to the Texas State Historical Association. He enjoyed a successful medical practice in Collin County but left it to pursue a career as an attorney. He joined the law firm of R. De Armond & Thomas Jefferson Branch and became a champion of education and railroad construction. In 1857, he was elected to the Texas Senate. Four years later, the Civil War began.

During the 1861 Secession Convention, Throckmorton stood with Sam Houston against secession. However, when wartime began, he abandoned this principle and enlisted in the Confederate army, leading the 100 member Company of Mounted Riflemen of Collin County in May of 1861, and eventually becoming a Brigadier General of Troops.

He only served as Governor from 1866 to 1867—the early, troubled days of Reconstruction. Texas was the state furthest removed, on the very edge of what was then the nation, and change here was notoriously slow. It’s why Juneteenth is celebrated; slaves in Texas were not officially informed of their freedom until June 19, 1865, two and a half years after the Emancipation Proclamation.

Throckmorton's statue was by a once-celebrated artist named Pompeo Coppini, whose work is scattered throughout Texas. Other works include the Alamo Cenotaph and the Littlefield Fountain at the University of Texas. According to the City of McKinney, it was donated in 1911 by the Federation of Women’s Clubs.

At a July 7 McKinney City Council meeting, a small army of citizens arrived to discuss the fate of the statue. They want to remove his statue not just because of his service in the Confederate army but because as governor, Throckmorton was a staunch opposer of the Fourteenth Amendment, which gave citizenship to everyone born in the United States, including former slaves and their families. It was one of three amendments passed during the Reconstruction era to establish rights for Black Americans. The 14th Amendment was key in landmark Supreme Court decisions such as Brown vs. Board of Education, which ruled that segregating schools was unjust.

According to Texas After The Civil War: The Struggle Of Reconstruction, by Carl H. Moneyhon, a professor of history at the University of Arkansas, in his inaugural address, Throckmorton on the one hand urged Texas legislators not to take action that would cause the North to doubt their loyalty, but on the other, encouraged them not to ratify the 14th Amendment. Legislators did as he urged, calling the amendment “nothing more than an effort to raise blacks above whites.” They voted 70 to 5 and rejected the 14th Amendment.

Throckmorton's advice that they not anger the North also provided Texas legislators with an easily walkable tightrope; they passed laws providing Black Texans with basic property rights, personal security and liberty, but denied them voting rights, forbid them from testifying in cases involving whites, and prevented interracial marriage.

Moneyhon writes that this attitude put Throckmorton on a “collision course” with the federal government. Throckmorton chose to ignore reports that landlords were cheating Black Texans as well as “cases where the civil government failed to protect the rights of freedmen.” He was eventually thrown out of office because of his resistance and because the support his state government provided for Black Texans was judged to be so lacking. He was further barred from holding public office ever again (until the General Amnesty Act of 1872 allowed him to return to Senate).

“The history of McKinney should be shared so comprehensively that it propels us into that future that is honorable," a McKinney resident told council members at the July 7 meeting. "Sadly as a standalone, the statue of James W. Throckmorton represents a one-sided time in the community when the civil rights of the whole community were not considered."

One question that consistently comes up in these Confederate statue cases: is how do we honor and condemn someone at the same time? How do we acknowledge his accomplishment at being McKinney’s only Texas governor, while condemning his participation in enabling and exhibiting racist attitudes during Reconstruction, allowing them to permeate the state government?

It's a question that the McKinney city council is still deliberating. As of yet, they have made no decisions. Similar to Denton County commissioners, they are forming a diverse task force of people to discuss issues included but not limited to Throckmorton’s statue. They will bring. a resolution to form the task force at its July 21 meeting.

“It’s meaningless to you, but to many of us, it isn’t," a young Black woman pointed out at their last meeting. "It is a sad reminder of our history. It’s not just our history, it’s American history."