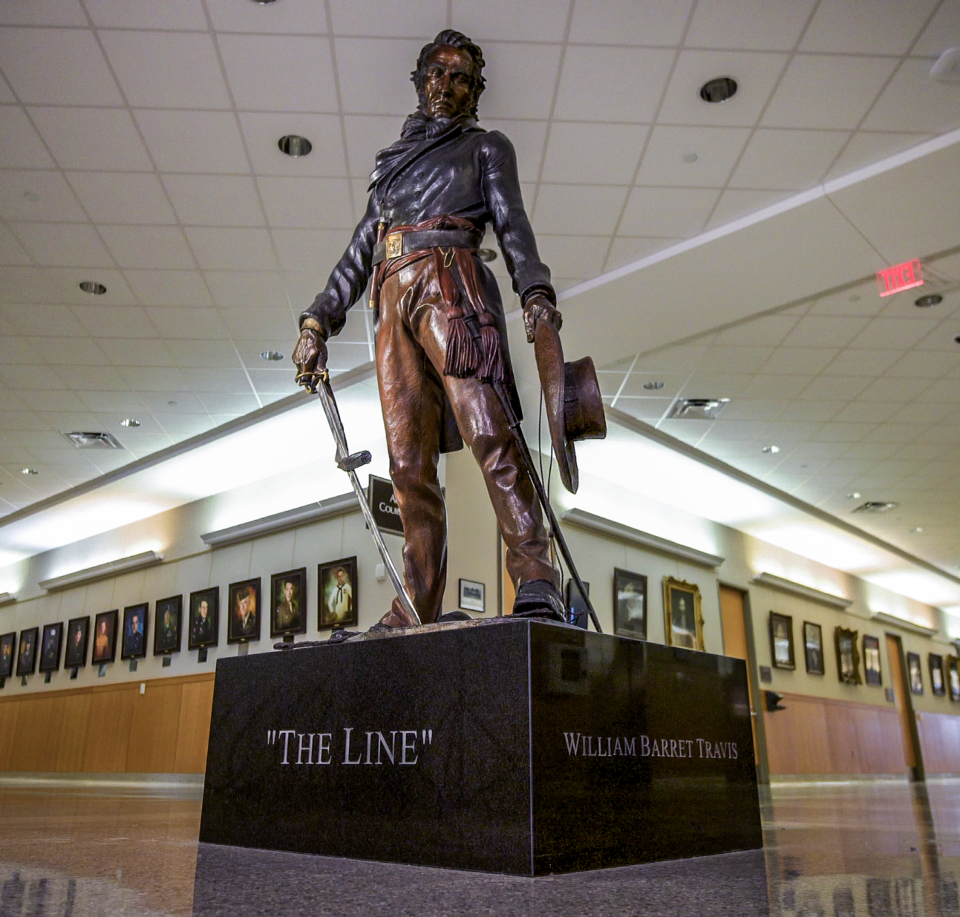

Alamo commander William Barret Travis has been drawing an apocryphal line in the sand with his sword for 13 years at the Collin County Courthouse. Standing tall, defiant, and forever frozen in bronze, Col. Travis appears regal like a swashbuckler from a Hollywood movie on his pedestal on the first floor of the courthouse, flanked by portraits of other heroes known for defending just causes.

Inside his workshop in Sedona, Arizona, James N. Muir, a former West Point cadet and veteran, sculpted more than 60 life-size statues, 13 of which were “Colonel Travis – The Line,” in lifelike detail. McKinney native William “Bill” Boyd, once the youngest elected district attorney in Texas, and his wife, Barbara White Boyd, a former investigative reporter, bought the statue when the new Collin County Courthouse was being built and unofficially loaned it to the county for display in 2007.

Local and visiting attorneys often gather around the Col. Travis statue, discussing issues not necessarily recommended for print. They refer to it as, “meeting at the statue.”

“It reminds us that in today’s world, everything is fast paced and we don’t reflect on our institutions and traditions,” says attorney Clyde Siebman, who joined with Barbara Boyd to make the loan official late last week. “[The statue] harkens back to a day when those things were more prominent. It’s also easy to forget that Collin County (like Travis) played a key role in the early days of Texas and the Republic of Texas.”

On Friday afternoon, nearly 50 people, many of whom were lawyers, gathered at Colonel Travis’ statue for its rededication ceremony, which also honored the late Bill Boyd and Homer B. Reynolds, one of the original co-founders of the Siebman Forrest firm in Plano, Dallas, and Sherman. It was the 184th anniversary of Col. Travis’ final stand at The Alamo.

Though Boyd had gained some wide-spread recognition for representing Tex Watkins, Reynolds’ recognition was more within the legal and business communities. Besides being a leader at the Siebman Forrest firm, he was also the co-founder of the Collin County Bench Bar and the Eastern District of Texas Bar Association. He lived by a Davy Crockett quote, “Be sure you’re right, then go ahead.”

Both Boyd and Reynolds died of heart attacks. Reynolds was 47 and Boyd was 71.

After Boyd’s death, Barbara White Boyd wasn’t sure what to do with the statue. Clyde Siebman says the Siebman Forrest firm has a keen interest in Texas history, and offered to help her bring a higher profile to the statue. They began working with the Collin County Commissioners Court to make it an official loan to the courthouse.

“It would have been tragic had it been removed,” Siebman says.

Many of those gathered at the rededication ceremony would have agreed. It’s not hard to understand why when you’re standing in front of Col. Travis whose eyes seem to dare you to take a stand for your beliefs and cross the line to stand with him in battle. Muir’s lifelike details bring him to life in the center of the Collin County Courthouse. Some of Muir’s other statutes include a 30-foot high Crucifix and Christ sculpture and the Confederate rider known as “The Last Horseman.” Muir calls the art he creates “Allegorical Art” and fills it with symbolic meaning. His art can be found around the country in public collections at West Point Military Academy in New York and the Gettysburg Battlefield Museum in Gettysburg.

Semi-retired Texas State District Judge Nathan E. White, Jr., the first Republican County Judge in Collin County, owns one of Muir’s sculptures, appropriately called “The Judge,” and mentioned it at the rededication ceremony Friday at the courthouse, where he served as the Master of Ceremonies.

He also discussed his first interaction with Muir several years ago when Judge White was visiting Arizona. He had noticed a statue of Col. Will Travis drawing a line in the sand outside of a small retail shop. Judge White asked the store owner about it because it was the same statue on the first floor of the courthouse. The shop owner told him that Muir’s workshop was just around the corner.

Judge White walked over to Muir’s shop but noticed it was closed. He called a phone number left on the door and discovered that Muir was in Richardson for a dedication ceremony for a Christ statue he had sculpted for a Baptist church. A couple of days later, Muir returned and they were able to visit, and Judge White discovered that Muir had sculpted a number of patriotic pieces, including a large one of the Sons of the American Revolution, which he called “Sons of Liberty.”

It is now on display at the Sons of the American Revolution headquarters in Louisville, Kentucky.

At the rededication ceremony, Judge White gave a talk about “connections” and pointed out not only his connection to Muir but also his family’s connection to Col. Travis. He discussed how people are connected by six or fewer steps. For example, Judge White told the crowd that he had shaken hands with former presidents Ronald Reagan, George H.W. Bush, and George W. Bush. Since they have all shaken hands with other world leaders, Judge White was now two steps away from being connected to those leaders, and the crowd at the ceremony who are acquainted with Judge White would be three steps away from them.

“[So] why do we have a statue of William B. Travis [at the Courthouse]?” Judge White asked. “He’s not from Collin County.”

Judge White motioned toward the portraits of the Collin County heroes surrounding Col. Travis’ statue and pointed out that like Travis, they had all drawn their line in the sand and dedicated their lives to defending a just cause in America’s wars.