At the age of 4, Peter Dadson knew one day he would help people. His dad a pharmacist, his mom a teacher; Dadson wanted to be like them. The kid from Cedar Hill wanted to make the world a better place, and he wanted to do it in a coat similar to his father’s: a white coat that bore his name in stitched letters across his chest. Dadson’s dream was to be a doctor.

“I wanted to grow up to help people, like both my mom and dad [do],” Dadson says. “I was drawn to the medical field.”

At the time, he wasn’t aware of the obstacles he would face, whether they be societal or institutional. He didn’t know yet that due to the color of his skin, his chances of reaching that goal were statistically unlikely. He was just a smart kid who wanted to save lives.

Dadson, now 17, is a senior at The School of Health Professions, a magnet school located in Dallas. Thirteen years later, his dream remains the same, and he’s off to a fast start toward realizing it. Dadson plans to be a heart surgeon, similar to a doctor from Carrollton that came to his school years ago as a speaker.

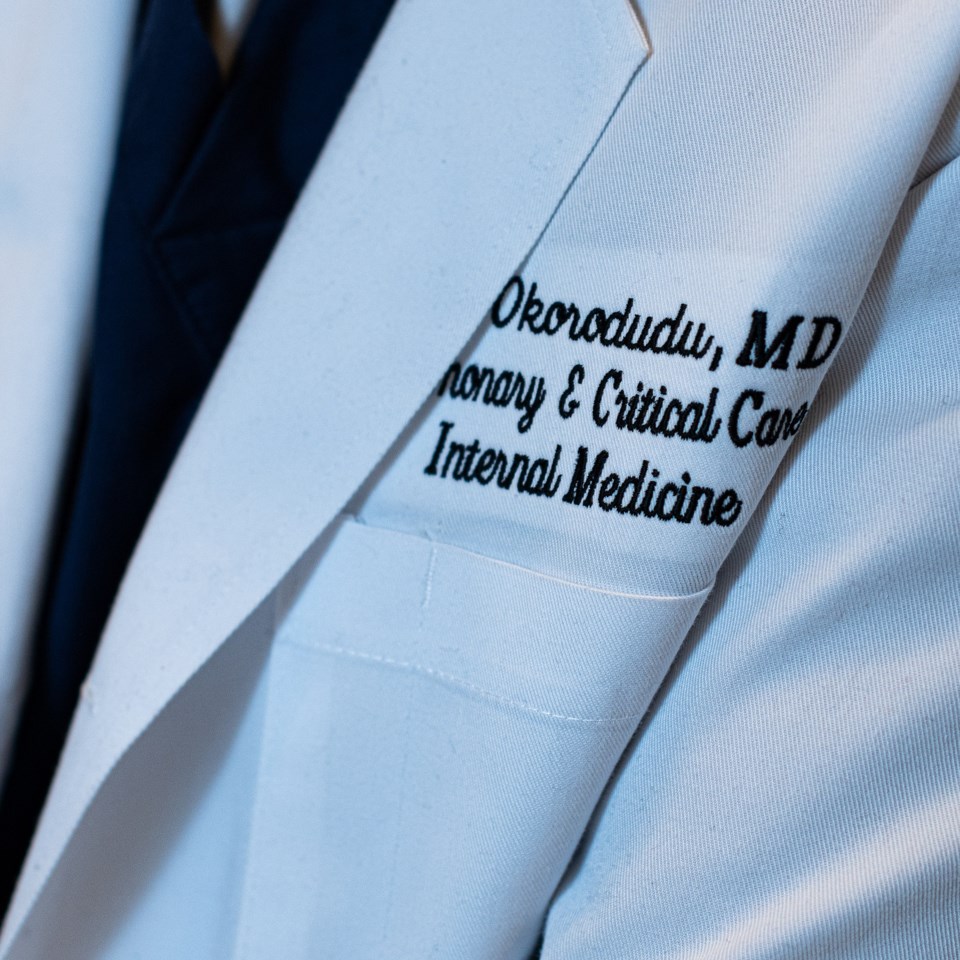

Dr. Dale Okorodudu is the founder of Black Men in White Coats (BMIWC), an organization he built to foster diversity in medicine through mentorship and motivation. When he spoke to Dadson and his classmates, Dadson was inspired, and his dream became a mission.

Dr. Okorodudu challenged the group of students in Dadson’s class with troubling statistics, drawn from studies conducted by the American Association of Medical Colleges, which found only around 2 percent of medical school applicants in the United States are black men. Furthermore, the rate of black males applying to medical school is declining despite rising rates in other fields of study.

“It was a call to action,” Dadson explains. “One of my favorite quotes is by Martin Luther King Jr. who said, ‘The ultimate measure of a man is not where he stands in moments of comfort and convenience, but where he stands at times of challenge and controversy.’ When I heard that statistic, I just wanted to take on that challenge and defy the odds.”

Dr. Okorodudu, or “Dr. Dale” as Dadson calls him, further inspired him to be a black man in a white coat. At the time of our interview, Dadson had sent out around 20 college applications. The next step along his journey, Dadson hopes, will take him to Harvard, Stanford, Yale, Columbia, The University of Chicago, or Southern Methodist University. Dadson knows it won’t be easy, but he’s ready for the challenge. The prize at the end, he says, will be worth it.

“[A white coat] would be one of my most prized possessions,” Dadson says. “The symbol of a white coat, while some people may think it makes you look smart, there’s … a deeper meaning to it.”

A white coat is not just a garment to Dr. Okorodudu either; it’s a symbol that carries weight, especially when it’s on the shoulders of a black man. A pulmonary and critical care physician, who specializes in treating lung ailments, Dr. Okorodudu has been shifting society’s stereotype of what a doctor looks like ever since he started as an undergrad at the University of Missouri. Early on in college, while on a flight home to League City from St. Louis, a fellow passenger turned to him and began a racially-tinged tirade.

“I was dressed in baggy clothes, it was how we used to dress back then,” Dr. Okorodudu recalls. “A woman sat next to me on the airplane, and she pretty much criticized me and ridiculed me throughout the flight based on the way that I looked, the way that I dressed, and the way that I spoke—essentially saying that I’m not going to be successful and no one’s going to take me seriously.” That woman didn’t see a doctor in a young Okorodudu. But he did.

The future physician didn’t let the ugliness of the interaction deter him. He didn’t let society’s view of a young black man, who happened to be dressed in baggy clothes on a long flight home, stop him from pursuing medicine. Instead, he turned it into motivation, and it has remained a powerful memory that has fueled his career and his mentorship efforts.

“That [encounter] was the primer,” he explains. “That made me question the way people in society viewed me, just judging me by how I looked without knowing how intelligent I may or may not be.”

Years later, he would recall that ugly day on the airplane when he first read the studies from the Association of American Medical Colleges, which found that black men made up just 2.9 percent of applicants to U.S. medical schools, and fewer black males entered medical school in 2014 than were accepted in 1978. The problem is complicated by several factors.

“The biggest thing is lack of role models,” Dr. Okorodudu says. “Lack of mentors in the field, individuals that look like them. We have a lot of young black men who have so much potential but they don’t see people like them in the medical field. You gravitate toward what’s like you and what’s around you.”

According to Dr. Okorodudu, exposing young children to the idea that they could be doctors, leading by example, is paramount. He wants young black men to see themselves as the men in white coats, and know the coat would fit.

Dr. Okorodudu first realized the power of a black man in a white coat for himself when he and his family gathered around the television to laugh at Dr. Cliff Huxtable on The Cosby Show, which started its 8-year run in 1984. Though the program remains a classic, its legacy has been tarnished, Dr. Okorodudu admits, by Bill Cosby’s recent conviction on three counts of indecent assault. But at the time, even now, the black nuclear family at the heart of the show, and the lifestyle they portrayed onscreen opened eyes. The idea of The Cosby Show was a hopeful one.

“It captured the culture,” Dr. Okorodudu says. He saw a black man that practiced medicine, a black woman that practiced law, and a thriving family living in a beautiful house. The fictional program gave kids like Dr. Okorodudu a glimpse of a new reality.

“Even though there weren’t as many role models, we had role models on TV,” Dr. Okorodudu says. “We had the ‘ideal, model family.’”

Today, there is no equivalent iconic figure or family being portrayed in pop culture. Dr. Okorodudu hopes to fill that void with his outreach, by sharing the real stories of black physicians, and providing resources for students, like Dadson, who are pursuing medicine.

Dr. Okorodudu has an established career, a strong mentorship program, and has created pathways for the next generation to follow in his footsteps. He established his future thanks to his studies, hard work and mentors who helped show him the way. He also credits role models like Dr. Ellis Ingram, an emeritus associate professor of pathology at the University of Missouri, who taught him the value of giving back, by taking him and other students to mentor local area youth, even while they were being mentored themselves.

His older brother went to medical school and his father, a Nigerian immigrant, had a PhD in Clinical Chemistry. Dr. Okorodudu had a support system. It wasn’t hard for him to envision himself as a doctor. But he was fortunate.

Based on statistics on medical school admission, the likelihood of anyone growing up and having been treated by a black male physician is relatively low, and Dr. Okorodudu suggests that the negative effects are widespread. African American men have the lowest life expectancy of any major demographic group in the United States and live on average four and a half fewer years than non-Hispanic white men, according to a 2017 National Vital Statistics report.

A study by the National Bureau of Economic Research found that black patients are more likely to feel comfortable with black doctors and more likely to pursue preventative, invasive procedures if administered by black doctors. The study also found black doctors are more likely to practice medicine in underserved communities. It’s part of why Dr. Okorodudu’s work inspiring the next generation of black doctors is so important. Encouraging young black men to pursue medicine will impact students lives, but also could lead to better health care for black men.

In 2011, with a team of like-minded physicians, Dr. Okorodudu founded DiverseMedicine Inc. which employed social media as a way to connect and mentor students. He started by filming himself, sharing his story and it grew from there, casting a wide net to Facebook, Twitter, YouTube and other popular social media sites of that time. “DiverseMedicine’s belief is that individuals from underrepresented ethnic groups as well as those from economically disadvantaged upbringings are capable of becoming highly effective clinicians and scientists if provided with a community of support and mentorship,” the website states.

A couple of years later, he founded Black Men in White Coats to serve as a resource supporting hundreds of black students through a mentorship program, highlighting the stories of successful health professionals and providing information about career-building opportunities. From podcasts, writing books, to organizing youth summits, public speaking, and practicing medicine—all the while juggling quality time with his wife and three kids—Okorodudu stays busy. Students like Dadson, who have come across BMIWC, and found a helpful voice in Okorodudu, see black men in white coats frequently.

Often, Dr. Okorodudu will be approached by former and current students, and seeing them succeed is his biggest inspiration. The knowledge that one life is changed, one student is sticking to medical school, one teenager has decided they want to be a doctor keeps him and his organization going.

“We typically run into people who say they were going to quit, that they weren’t going to pursue medicine anymore, but they started paying attention to what we were doing and that’s what got them through,” Dr. Okorodudu says. “It’s great. It’s good to know we’re having an impact. Knowing when these individuals come to us and say what we have done has touched their lives.”

When Dadson eventually heads to college, he will carry along some lessons in his pocket. Dadson has an acronym typed out in his phone—GRIND: Goals, Reason, Information, Network, Discipline. They’re lessons he learned from Dr. Dale over the years that Dadson says will help him defy the odds, giving him a mindset that will prepare him for anything, including medical school.

“Dr. Dale said getting information from a lot of places is like a faucet, you can control when you want it. But in medical school, it’s so exhausting,” Dadson admits. “It’s like trying to get a cup of water from a fire hydrant; you have no control over it. That can have a heavy toll on a lot of people. Getting through the grit and grind, having that tenacious mindset will get you through. And once you reach the end of the light in the tunnel, it will feel amazing.”

Originally published in the February 2020 issue of Local Profile.