In the blue morning light, Elsie Holdbrook sits at the bedside of a dying woman and watches over her. Family members crowd the kitchen and the fridge is stuffed with meals from well-wishers. They fill the house from time to time, which is usually only this crowded on holidays.

The woman hasn’t slept in her own bed for weeks, instead she reclines in a hospital bed by the window, an oxygen mask over her face. She hasn’t been able to walk for months, but enjoys visits from friends and family. Some she hasn’t seen in years. Elsie has come to love the woman at a professional distance, while she has bathed her, fed her, and watched over her.

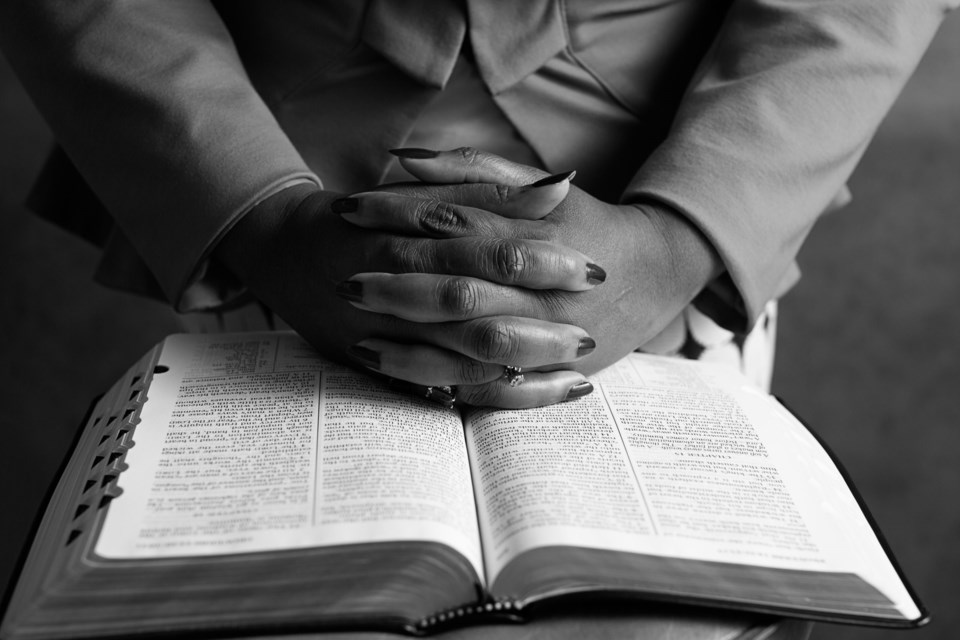

Almost overnight, however, the tone changed. Today, she isn’t asking for visitors or for Elsie to read to her from her weathered Bible. All she wants to do is rest; she doesn’t even want to eat. When her daughter comes in, she squeezes her hand weakly and in a voice as thin as a thread, says that she loves her. Her fingertips are tinted blue. Elsie knows that the time has come. She also knows that it’s okay. There isn’t much left for Elsie to do. Her patient may not respond much, but she still feels comfort and pain. If she wants food, Elsie will make sure it’s the best food. If she wants her hair washed, Elsie will wash it. If she wants nothing at all, then Elsie would be there anyway, keeping her clean and comfortable.

Elsie describes caregiving as a “very sensitive thing.” To her, end-of-life care is much more than the day-to-day of keeping someone clean and managing their medicine. It’s about connecting with a complete stranger despite any differences—wealth, religion, skin color—and walking alongside them in their time of greatest need. It’s like having a twin, someone who thinks ahead, anticipating whatever you might need.

“I become your eyes, ears, everything to assist you,” she explains. “I assist my patients in being their best selves at that moment in time. For some, it is a job. For me, it is a calling.”

Elsie wasn’t always a caregiver. “I never thought I could be soft enough,” she admits freely. In what feels like another lifetime, she worked in “Corporate America,” specifically in credit bureaus and mortgage companies. However, talking with people who needed money and help she couldn’t give made her feel trapped.

Then in 2007, Elsie’s father died suddenly of a heart attack. It was shock, so quick that he didn’t get a chance to say his goodbyes. In the aftermath, Elsie wondered what his quality of life had been like in his last months, if he was eating right and taking his medication, if some little detail had been ignored that could have prolonged his life. One fact stayed with her: no one had been there to help him.

“When my dad died I saw a huge area of life that was neglected, and so many people in pain, with no advocate to speak on their behalf,” she explains. Once she saw it, she couldn’t ignore it.

Over 11 years as a caretaker, Elsie has a reputation for taking on “difficult” patients—strong men and women who demand a lot from their caretakers. She has cared for former professors, veterans, teachers, doctors and lawyers. Sometimes they have very strict rules and often they test her. One patient insisted that she recite the Lord’s Prayer and Psalms 23 to prove she was actually a Christian. But Elsie takes it all in her stride.

“It’s better to admit you don’t know what you’re talking about than to try to be smart with false information,” she chuckles fondly. “They’ll shut it down. You can’t lie to them. But I get to be their advocate. I’m in the presence of greatness.”

The key to care, she says, is to come into people’s lives gently, without micromanaging them, and to remain cognizant that every patient is different. It’s about walking the “fine line between being assertive and giving them room to be themselves.” The caregiver’s job is to preserve their lives through proper hygiene, fall prevention and elevating their quality of life. Sometimes they pass the hours playing chess, taking walks or writing letters. Sometimes she helps them shower, fixes their hair and takes them out to lunch, to the bank, to the library to return books. As much as she can, she keeps the focus off of the life they are losing, and on what they still have left.

Plano: A brief account of how we got here

“Don’t take their power. You are there to assist them in their day to day in what they want to do. You aren’t there to judge, complain or correct, but to assist. If they’re still here, they’re here for something, to teach, to unload what they had, pass on the torch,” she says. “I’ve taken a professor to his old college to see a game and have lunch with his old colleagues. He feels bad that he has to go to the bathroom and that he has to bring me in there with him, but he gets to have lunch with his colleagues. He gets to be in his favorite restaurant and for that minute, it feels like the world is okay. He’s normal again.”

She considers it her job to be so present and prompt that they don’t feel the difference in their lives. One of her fondest memories is of taking a patient to his favorite diner for a simple breakfast of orange juice and pancakes.

“He’s not supposed to eat those things,” she admits. “But he wants to eat them. Yes, he’ll have diarrhea all day that I’ll have to clean all day. But he loves it. He’s earned the right to enjoy pancakes one last time. He might never eat them again. It’s not about me. It’s never about me.”

It wasn’t always that easy. She describes the beginning of her career as as being “thrown to the wolves.” She hadn’t been at all prepared for patients who would hate her because of what she represented, the loss of their independence, or those who would grope her or fight when she tried to bathe and feed them. No one had told her about the saddest cases, when patients linger, bed-ridden for years with rare visitors.

Elsie knows other caretakers who have been liable for a patient’s death because of bad care. It only takes a five-minute bathroom break for an elderly person to have a bad fall that pushes their life expectancy from five years to two weeks. It took four years to learn the most important lesson caretaking has taught her.

“For me, the fundamentals of caregiving have to do with being centered with God. You must be centered and you must have a tough skin,” she says. “If the person is mean, I respond with love. If they’re angry about their condition, angry that all their friends are dead, angry because they have argued with their children—it’s not about me. It is never about me. So why don’t I make today a good day?”

Along the way, she forms unique bonds with her patients who tell her things their own children will never know, express fears, final hopes and longings no one else hears. Many have come to view her as another daughter. They know that she will never exploit or hurt them. They’re at their most vulnerable, but at all times, there is trust between them and through that, their dignity is preserved. Yet every time she wants into a patient’s home, she puts a piece of herself aside. She can’t be emotionally attached because she knows that her job will end—in weeks, months or years—with her patient’s passing. Sometimes it will be sudden during the night, or the progression of a terminal illness. Often, it’s natural.

“[In those cases] death is a time when someone says, ‘It’s okay now. I want to go,’ It’s a choice,” she says. They’ll stop eating, stop drinking water and begin to refuse visitors and very quickly, the body begins to shut down. “The day you die is when you decide. I can’t do anything but hold their hands and say, ‘It’s okay.’”

She remembers one man who she cared for years. Suddenly, one day, his daughter had arrived out of the blue. They had been estranged for 20 years. She approached gingerly, unsure of her welcome. But he’d needed to say goodbye to her, needed to know that she was okay, that they had forgiven each other. Ten minutes after she arrived, he passed away. He had simply needed to see his little girl again and know she was all right. Often, that’s the question—whether everyone is all right. Elsie sees it happen all the time. Her patients are usually in their 80s and 90s. They’ve lived their lives. They’re ready.

There is, Elsie says, beauty in the transition. “It makes you present in life. Tomorrow is not promised. These people are dying. No amount of money can save them. Most of the time, they’re dying alone with just a caregiver, just me at their side. But the beauty of it is they’re peaceful. They don’t know what’s happening. Love people as you want, fight it as you may, and when the time comes, it comes. Time doesn’t go back. It goes forward.”

After the death of a patient, Elsie takes a few months off to purge herself of everything she has suppressed, to fully be herself. She waits until they’re at peace before she allows herself to grieve. “I’m happy that I was able to help their transition,” she says. “But I loved this person. I loved taking care of them.”

Once, after a patient passed on, she went to visit the woman’s hometown in Oklahoma. She’d talked about it often in their time together and Elsie wanted to see why it had meant so much to her. “They have good food there,” she says, beaming. “Good Southern food. I saw why she talked about it the way she did.

“If more people are living longer now, we need people who are passionate about care. Care has opened doors for me. Care has exposed me to places and people I never would have met. I have taken a patient to the Meyerson—in my regular life, I’d never have the opportunity to go to the Meyerson. It is through care that this door was opened for me.” She smiles. “Care is the center of our lives. It changes the trajectory of people’s lives. It’s an honor.”

![Top 5 Reads Of The Week [June 23-27]](https://www.vmcdn.ca/f/files/localprofile/images/events/downtown-celina-city-of-celina.jpg;w=120;h=80;mode=crop)