Traffic whizzes by. If you ignore that, it’s peaceful, almost serene — horses grazing while farmers patch part of the fence, the cool wind blowing my hair and the smell of wheat. Near the entrance of Brinkmann Ranch, just off Preston Road and Frisco’s Main Street, is part of an outpost for Preston Trail’s original path. It seems fitting for a piece of Texas’s history to now be a lively farm.

Yet part of the historic route remains simply something of the past, and we may never know exactly where the trail began. Due to towns ceasing to exist and new ones beginning, Preston Road has changed over time and does not follow its original path.

I take the same route every day — this route, passing through the same stoplights and seeing the same landmarks. But what I didn’t know when I started making the drive was that every morning, I am driving over a piece of deep Texas history.

Preston Road is the oldest north-south road in the state and a commonly used commute from Collin County to Dallas. The commercial highway of Preston Road, the namesake of the original trail, stretches from Dallas through Addison, Plano, Frisco, Celina and Prosper.

Preston Road was known by many names: the Buffalo Trail, an Indian Warpath, the Austin Road, the Kansas Trail, the Cattle Trail, Whiterock Road and the Texas Trail. But most of us know it as Preston Road.

Then

“This will tell you everything you need to know about the history of Preston Road,” Donna Anderson, a historian at the Frisco Heritage Museum, tells me as she walks down the length of the mural just inside the doors of the museum.

Lebanon on the Preston is not only a book from the 1950s but also a tool used by the museum. The book by Adelle Rogers Clark offers a glimpse into the vast history and past of Preston Road.

A quote from Lebanon on the Preston welcomes guests to the Frisco Heritage Museum, relating the many names of Preston Road with a mural depicting the history of the route. From horses and cowboys to trains and buggies, the mural shows the road’s progress through time.

At the beginning of the 1800s, Preston Road was part of a Native American trail that extended from St. Louis, Missouri, to Mexico, parts of which were originally known as the Chihuahua Trail and the Shawnee Trail. During those early years, heavy rainfall created a spine that followed the trail, flowing from the Elm Fork of the Trinity River and draining into the East Fork of the Trinity River until the rivers merged downstream of Dallas, creating the perfect fortress for a Shawnee village on the Texas side of the Red River.

What was then known as Preston Trail, named after Col. William G. Preston, who built a fort where the trail crossed the Red River, became part of the first official Texas military road in 1839.

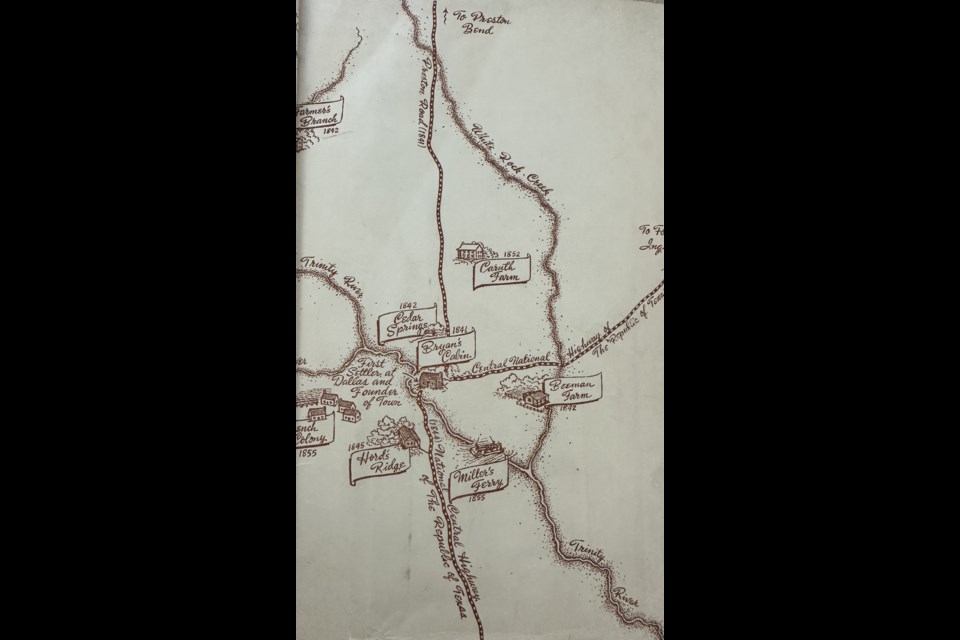

Photo courtesy of Heritage Association of Frisco

Anderson takes me down the stairs of the museum and quickly points to a drawing of a map showing the original trail. The aged drawings now look dark, and it’s hard to make out what we now call Preston Road. “Over time, the road has shifted from where the trail was,” Anderson tells me as she points to the early map of Collin County. “It straightened out and became what we know today.”

At the start of 1840, and the beginning of the railroad, the newly named Old Preston Road was a hot spot for immigrant transportation into North Texas. At the time, the land was free to settlers, 640 acres to a married couple or 320 to a single settler, causing an influx of new residents, primarily immigrants. But life for those settlers wasn’t as easy as getting free land. After years of disputes between Native Americans and settlers, a treaty was signed in 1843 to prevent more violence, increasing the traffic on Old Preston Road. In the same year, the railroad was completed by soldiers under the command of Col. Cooke, with the road starting near the community of Preston Bend in present Grayson County. Longhorn cattle marched up and down the road, but as other cities began to flourish in 1870, cattle trails ventured farther west.

“No one will ever be able to estimate the number of people who have traveled Preston Road. Many wore moccasins; some were clad in boots; some were swift, some were slow,” reads an excerpt from Lebanon on the Preston. “Some came from Europe, others from Canada and Mexico.”

By the early 1900s, horses and buggies began to cover the road, and development furthered in North Texas. Many of the travelers were coming and going from Lebanon, which no longer exists today — instead, a single street by the name of Lebanon is the only reminder of the bustling city. Three miles northwest of Lebanon, a new town by the name of Frisco was formed. Most residents of Lebanon picked up their businesses and relocated to the new town.

“In 1902, most of the people who lived in Lebanon moved to Frisco,” Anderson said. “There were more means for the economy.” Three years later, the post office in Lebanon closed, sealing the fate of the long-forgotten town.

As we continue to walk through the museum, Anderson shows me two pictures of what used to be Lebanon, boys on bicycles and longhorns being guided down the road, which show only a glimpse into what used to be a lively town. As North Texas continued to grow, Preston Road did as well. Businesses and communities began forming around the road with easy access to neighboring towns.

Lebanon was a “wild and wooly” area of North Texas, according to Anderson, who looks around and lowers her voice when discussing the controversial topic. Brothels, disguised as massage parlors and lively taverns, operated in the city and later mushroomed in neighboring Frisco and adjacent towns until the 1990s. But the town worked to clean up its image and rid the town of the parlors by removing alcohol and making Lebanon dry. “There was a reputation,” Anderson said, laughing. “Mamas were telling their boys, ‘Don’t be stopping in Lebanon.’”

That reputation lasted quite some time. “There were probably five or so that I remember,” former Frisco Mayor Maher Maso later tells me over a pita bread and tzatziki appetizer at a Greek restaurant off Preston Road. “There was the Dollhouse, the Body Shop, April’s, the Tub Club and Michelle’s Ranch.”

According to the former mayor, some of these “massage parlors” lasted into the late 1990s. But because the area was unincorporated, the Collin County Sheriff’s Department was dealing with more serious crimes, and the city was slow to shut them down.

“The county sheriff has a lot of space to cover,” Maher said while sipping on iced tea. “They knew that, and that’s why they were there.”

But as families moved into town, the brothel business slowed, and only a few on Preston Road remained into the 1980s and 1990s. “Families started coming into the area, so they started closing or moving,” Maso explained. “You didn’t want families going into the Dollhouse expecting to buy a toy.”

Even though the history of what occurred on Preston Road isn’t always as innocent as we may think, the area has proved to be an iconic route of transportation for hundreds of years.

Now

“When I got here in 2007, Preston Road north of Main Street was still a two-lane blacktop,” Anderson said. “Now, Preston Road has six lanes and more traffic than many highways.”

The Frisco Heritage Museum has worked not only to preserve the history of Frisco but also to teach the new generations about how far we have come. Anderson is a historian at heart and has spent her time in Texas since 2007. She expects the areas surrounding Preston Road to continue to grow and discusses how much it has changed since she moved here.

Anderson explains that, even though development is good for the city, these changes make it more difficult to preserve the history. Though many residents in Frisco are helping the museum with the preservation process by doing their own research about their properties.

“We had a house-flipping couple call us a while back to ask if there was any history to a house before they began renovating,” Anderson said. “As it turned out, it was the first house of the first mayor of Frisco in 1902. The developers went to a lot of trouble to keep some of the original work.”

Eventually, Anderson and the Frisco Heritage Museum will place historical markers on important places on the Shawnee Trail to remind residents and travelers of the importance of the now-paved road they travel daily.

The rich history of the trail lives on through the places built near the site. Preston Ridge Campus, Preston Trail Farms, the Center at Preston Ridge, Preston Trail Community Church and many more will be a long-standing reminder of where we, as Texans, began, and where we will go in the future. So next time you’re stuck in traffic after a long day of work, take a minute to appreciate the past of Preston Road and all those who made the trek before us.

I think about it as I sit here at the long stoplight intersection of Preston and Belt Line on my way home from the museum. I wonder how many people have walked, ridden, or driven on this same path before me. The light turns green, and I turn off Preston with the question still lingering in my mind.