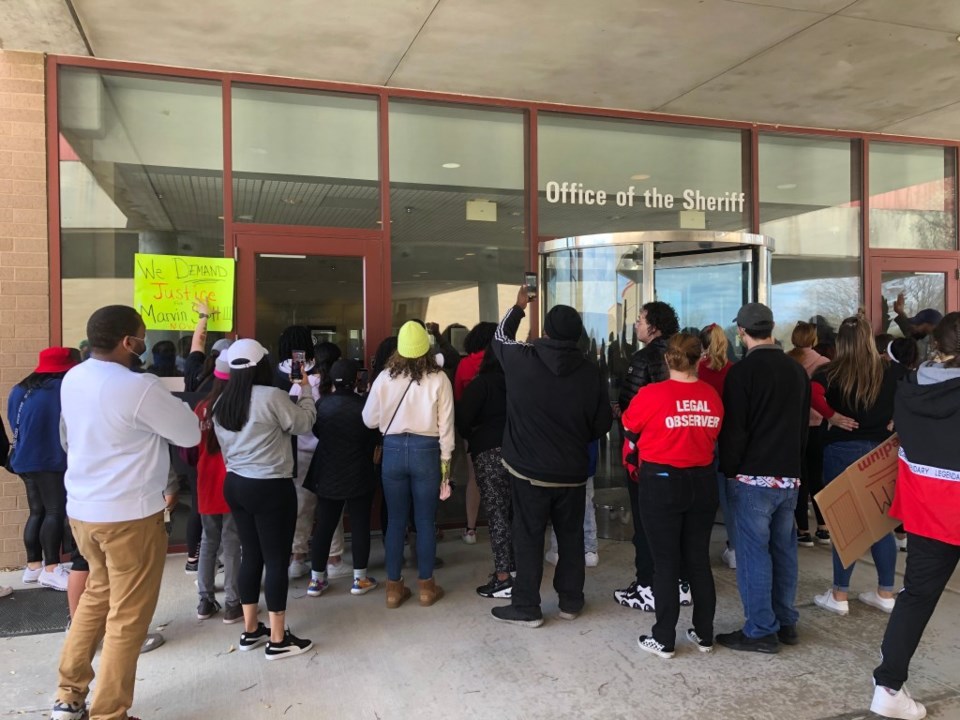

At 9 p.m., the green grassy hill looked almost black, and the sky above was filled with stars as LaChay Batts, sister of Marvin Scott III, gathered with about 50 protesters in a circle behind the Collin County Jail. Wrapped in blankets, they held signs that read, “We demand justice for Marvin Scott III now” and “Black Lives Matter.”

LaChay explained to the protesters that she wanted their planned demonstration — blocking the jail’s back entrance to keep others from being locked up until her family got justice — to stay peaceful.

“You are able to use your body as a blockage to this door for them… Y’all just try to keep it peaceful,” she said.

The protesters sat around a small campfire and played "Two Truths and a Lie," an icebreaker game usually reserved for first-day-of-school introductions. Two men bundled up in multiple jackets and wearing sunglasses approached the group of protesters, holding a speaker and microphone. They played Marvin’s favorite song while everyone waited for a bus of prisoners to come around the corner.

“Peace is not the absence of anger,” federal civil rights attorney Lee Merritt said to the crowd. “It’s not the absence of tension. This mom, this family has called for peace, and we are going to be peaceful, but peaceful doesn’t mean not to be bad. The actual definition of peace is the presence of justice. Then we have peace. Because we’re not at peace when they kill.”

LaChay stood off to the side of the protesters against a wall smoking a cigarette. She listened, but it was obvious she had a lot on her mind. She was only there because her older brother, Marvin, died on Sunday, March 14 while in custody at the Collin County Jail.

He’d been arrested earlier that day for a misdemeanor marijuana charge. Marvin had been allegedly smoking a joint near an outlet mall in Allen and mumbling to himself when Allen police arrested him. Merritt alleges that Collin County Sheriff’s jailers killed him later that night. He was only 26.

Merritt, who recently announced his bid for Texas Attorney General, had been talking about her brother on and off Facebook and for most of the day Thursday. But on this Thursday evening in late March, he told the story of a man named Patrick Warren Sr., whom Killeen police killed in early January. Warren Sr.’s son had called a mental health hotline because he was having a mental health break, much like police said LaChay’s brother was. A police officer came on the scene and shot Patrick Warren Sr. to death on his front lawn in front of his family. Warren Jr. drove all the way to McKinney to join the protesters and share his father’s story, pointing out that great injustices occur when law enforcement aren’t properly trained to handle mental health crises.

“Me, my mother, my brother, family friends — we were all on the porch, and we watched them murder my father while we screamed,” Warren said. “It’s super traumatic. It’s not something you get over. It's something that you got to deal with every day.”

Warren Jr.’s story is a familiar one for LaChay and her family. Allen police could have ticketed her brother and taken him to a mental health facility where trained mental health professionals could have helped him. Instead, they arrested him and took him to jail for a ticketed offense.

Arrest and jail for low-level marijuana offenses seems to be the go-to move for law enforcement — not just in Texas but around the country. It also disproportionately affects Black men like Marvin more so than white men, according to the ACLU’s 2020 report “A Tale of Two Countries: Racially Targeted Arrests in the Era of Marijuana Reform.”

Now Lachay’s brother is dead. Seven detention employees — a captain, lieutenant, two sergeants and three jailers — have been placed on administrative leave. The family wants the detention employees arrested and held accountable for Marvin's death. But the protesters say that the Scott family may not receive justice from a judicial system that values law enforcement lives over a Black man’s, especially ones like Marvin who struggle with mental health issues.

Marvin’s Death

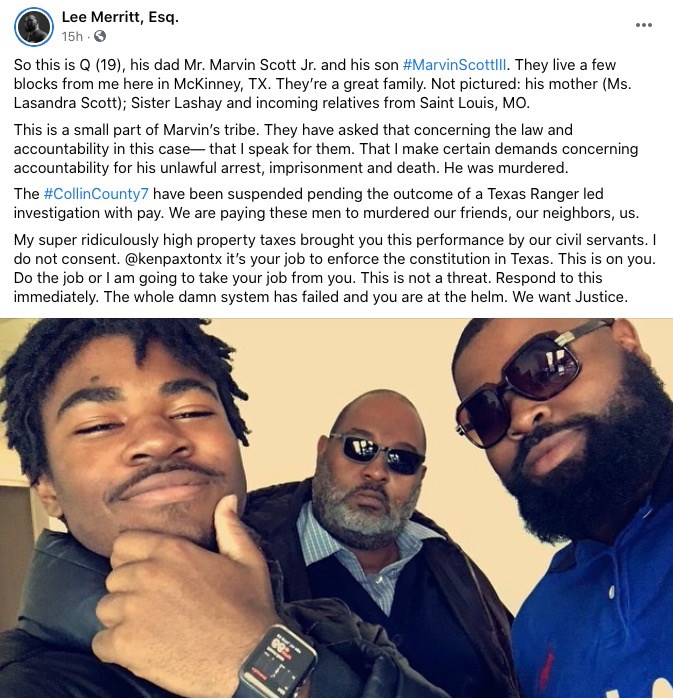

Marvin Scott III was known as a “gentle giant.” He was also a high school football player, a straight-A student and came from a great family who lived in McKinney, not far from their attorney Merritt.

At a protest earlier Thursday in front of the Collin County Courthouse, Marvin’s good friend Renel Blackburn recalled that Marvin was the only one there for him when he was hospitalized for mental illness. Marvin was also the only person who kept up with him after he left. Blackburn said he had just seen Marvin the day before he died: Saturday, March 13.

“He was just having fun,” Blackburn said. “He just having fun. He wouldn’t hurt a fly. The biggest teddy bear.”

On Sunday evening, no one was there for Marvin when Collin County detention officers started to process him, and he began having what police describe as a possible manic episode. In a March 18 Facebook statement, Allen police said that officers took him by ambulance to Texas Health Presbyterian Hospital. He spent three hours there and received the all-clear from the doctor. He was then processed at the Allen police headquarters and transported to the county jail for possession of under two ounces of marijuana.

A few hours later, he would be dead.

Collin County's Response

At a Friday morning press conference, Collin County Sheriff Jim Skinner said they accepted Marvin into custody at 6:22 p.m. Sunday. While in the booking area, he began exhibiting “some strange behavior,” Skinner said. According to Marvin’s friends and family, he had schizophrenia.

Instead of contacting a mental health professional, several detention officers tried to secure him to a restraint bed. They also used pepper spray on him and put a spit mask over his face. He became unresponsive, Skinner said, while he was being put on the restraint bed. Detention officers and nursing staff immediately gave him emergency medical attention and called an ambulance. He was taken to Baylor Scott & White in McKinney, where he was pronounced dead.

Leigh Ann Nolen from the Collin County Medical Examiner’s Office told Local Profile that Scott’s autopsy report is not complete yet and to check back in 8-10 weeks. Skinner declined to share any more details about the case until the Texas Rangers finish their investigation.

“I responded to the jail myself,” he told reporters Friday morning. “As you might imagine, I was broken-hearted to learn that someone had died in our custody.”

Blackburn and Marvin’s family are more than broken-hearted. They are angry, and they hired Merritt to represent them. Some of his high-profile cases include the 2019 shooting of Atatiana Jefferson, a Fort Worth Black woman who was killed by police, and the 2020 murder of Ahmaud Arbery, a Black man who was killed by racist would-be vigilantes while jogging.

Marvin’s father set up a GoFundme page seeking help to cover his son’s funeral expenses. He has raised more than $40,000 of the $15,000 he initially sought. On Wednesday, they held a prayer vigil for him at Town Lake Park, where they released balloons with 200 people who showed up in support. Protests followed Thursday afternoon and Thursday evening. And they plan to continue until they, hopefully, receive some kind of justice.

Blackburn demanded this justice Thursday afternoon at the protest in front of the county courthouse. “I’m done. I’m done being compliant,” he yelled into a megaphone to the crowd of protestors. “I’m done being resilient. You need to understand this is going on all across America.”

Marvin’s mother, Lasandra Scott, was quiet for most of the protest. And while she was wearing a mask the entire time, she couldn’t hide the pain in her eyes. She didn’t speak up until she heard that protesters could get arrested Thursday night for blocking the back entrance, where her son walked into the jail and never came out.

“This has to be very spiritual for me,” she said. “I lost my son, and it’s been very, very emotional, okay. I don’t want anybody to get hurt, anybody to get tear-gassed or anything. The purpose of this protest is peace, and we just want the seven officers’ names. And we want them to be arrested. You know, that’s what this is about.”

LaChay agreed with her mother. “I don’t recommend nobody going to jail,” she said. “This should be real peaceful. I just want justice for my brother. So just do the right thing when y’all come tonight. That’s what I want. I’m pretty sure my brother wouldn’t want to see anybody in jail.”

The Aftermath

As time went on Thursday evening, it became apparent that the police were aware of the demonstration and taking prisoners through another entrance. At one point, LaChay led the protesters to the jail’s front office as she had done earlier that day. Again, nobody came out. If one hadn’t known better, they would’ve thought the entire jail was vacant.

Inmate arrest records from the Collin County Sheriff’s Office show that arrests were made throughout that night. During the time protesters stood there, 12 arrests were made between 9:13–11:27 p.m. But no one knows where they entered the building.

Disheartened, protesters walked back to the back entrance, visibly getting colder as more and more people huddled together under blankets. Merritt said they would keep meeting at Town Lake Park every night at 9 p.m. until Scott’s funeral on March 30. There was hope in his voice that, by then, they would have the names of the seven officers.

So the protesters and Marvin’s family all waited outside the jail, shivering in the cold until 11:30 for that bus full of prisoners.

But it never came.

And neither did the names of the seven officers.