Every night Janelle Hofeldt sits at her computer, logs onto the Bring Typhenie Johnson Home Facebook group, and lists off the information that by now is as familiar as her own name. Typhenie’s description, height, weight, tattoos, and the number of the anonymous tip line.

The posts are bare, utilitarian facts. Janelle doesn’t say that Typhenie was a tomboy growing up. She doesn’t write that at 3 years old, Typhenie learned to ride a bicycle and she was roller skating by 4 years old. She doesn’t say that Typhenie’s favorite animals are elephants and penguins. There isn’t room for all of the colorful details of her niece’s life that Janelle clings to.

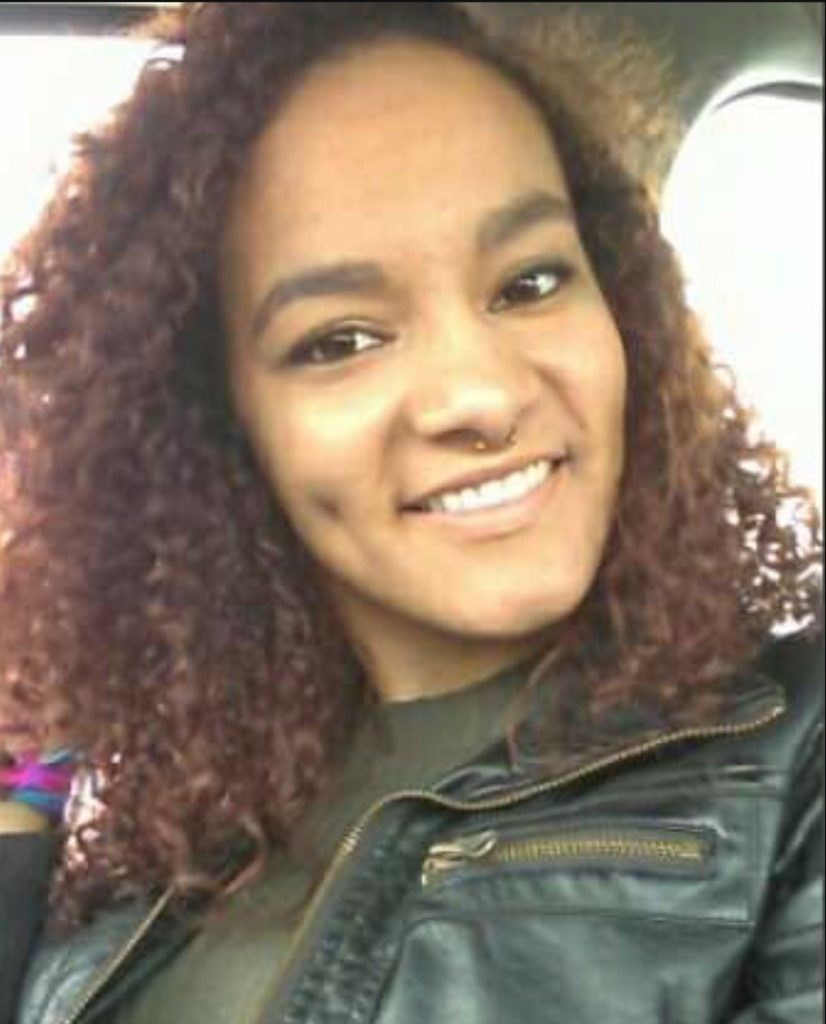

She chooses a picture to go along with it, scrolling through selfies Typhenie took and family pictures for one she hasn’t used in a while, and publishes the post, hoping that maybe tonight, the right person will see it. Maybe tonight, something will change.

“This helps me,” she says. “Ever since this happened, it’s like our lives just stopped. She’s out there somewhere.”

These posts, and her memories, are all she and the rest of the Johnson family have of Typhenie. She disappeared in 2016 and no one has seen her since.

90 Minutes

At 25, Typhenie—“Typh,” “Pippy”—Johnson’s life was just beginning. Typhenie has always had an outgoing spirit, her aunt says, and a beautiful smile. “Those dimples,” she adds fondly.

Typhenie is the youngest of four children. Her fraternal twin brother, Asher, was born just 14 minutes earlier. She and her brother, Iowa transplants, shared an apartment in Euless, Texas, where she had a job in the field of insurance. Janelle remembers that Typhenie and Asher were hoping to buy a house.

One day in 2015, Typhenie met a woman through the oddest of circumstances: they both realized that unbeknownst to both of them, they had been dating the same man. He was summarily ditched, and, perhaps as a gesture of goodwill and friendship, the woman introduced newly-single Typhenie to her brother, Christopher, around the turn of the new year.

Christopher, who sometimes went by “C-Note” or “Big Chris,” was in his early 30s. His most distinctive features are the numerous tattoos visible around his collarbone and neck, and up behind his left ear. In a photo of the two of them, Typhenie’s expression is very frank, almost serious, and Chris has tucked Typhenie close under his chin, half his wide smile buried in her hair. When they started dating, he was fresh from serving three years in jail for burglary with intent to commit assault. He had been released on parole in July 2015 and was staying at his parents’ house.

Janelle remembers meeting Chris once, when she came to visit her niece and nephew for a week in August 2016. They ran into him at a gas station by chance. “He showed up, just off work, and he was very shy,” she remembers “Tattoos don’t mean anything to me, but I noticed he had two tear drops and weird markings on his neck. I didn’t know what that meant.” Throughout the rest of the week, however, he didn’t impress her. Typhenie’s car had been giving her some trouble, particularly her brakes, and at one point, Typhenie asked Chris to look at some cars with her.

“He told her, ‘Can’t you see I’m busy? You can do it by yourself.’ He was busy playing a video game,” Janelle recalls coldly.

After the visit ended, Typhenie’s car troubles continued. It wasn’t long after that Janelle and her husband sat on the phone with Typhenie, trying to walk her through a repair job on her brakes while Typhenie struggled to work with the heavy parts. She’d asked Chris to help her, but he wouldn’t. Finally, she gave up and decided to hire a mechanic to look at it.

One August day, Typhenie asked her aunt how to break up with someone. Janelle suggested she ask for a break and say she needed space. Before the end of the month, Typhenie tried to do just that: ask for a break. But Chris kept coming around.

“They broke up,” Janelle says. “He’d keep coming back. He got jealous. Typhenie is very pretty.”

Despite Chris hanging around, Typhenie was moving on with her life. On the night of Oct. 10, 2016, she, Asher, and his girlfriend, Jessica, were all at the apartment they shared making a late dinner. Typhenie had a new friend coming over.

But Chris showed up to pick up some of his things left in the wake of their break up. Some outlets have reported that Chris had been invited over to watch Monday night football with Asher, but the Johnson family says that was not the case.

“She was about to have someone come over and her ex is here,” Jessica, who worked with Typhenie at the insurance company, would later testify. “It was just confusing. We didn’t know what to do.”

Typhenie wanted to avoid conflict. She and Chris went outside to talk. Later, Asher would tell police that the conversation was yet another attempt by Typhenie to tell Chris that the relationship was over. She didn’t bother to put on shoes, walking outside in a black sports jacket, a pink shirt with the word "Pink" on the sleeve, black and white spandex pants, and black ankle socks. Likely, it wasn’t meant to be a long conversation. She had dinner plans. They stood outside beside Typhenie’s car, close enough that they were visible from the balcony of their apartment, and snatches of their conversation could be heard.

During the discussion, Typhenie’s guest came downstairs to check on her. He’d tell police and her family that he approached them, but Typhenie told him to go inside. He waited in the apartment with Asher and Jessica, and they continued to monitor them from the balcony, just to make sure Typhenie was alright. About 20 minutes into the conversation, Chris and Typhenie moved to the side of the building, out of sight, and kept talking.

Forty minutes after Typhenie first stepped outside, Chris arrived at their apartment door alone. He told them that Typhenie had gotten into a vehicle with someone and driven off. Chris didn’t stay, but grabbed a couple of his own possessions and left. It didn’t make sense. Why would she leave when their plans for the evening hadn’t even begun? Sensing something was wrong, Asher tried to call Typhenie’s cell phone. When she didn’t pick up, he went outside to look for her.

Chris was still there. He had moved his white 2003 Ford Taurus to the side area of the apartment, backing it up onto the grass by the building with the doors open, where he and Typhenie had been talking. He was looking down into his open trunk. Asher, worried he had a weapon, didn’t approach, but watched Chris close the trunk and doors, and drive away. Only then, did Asher walk over to the spot where Chris had been parked. There, tangled in the grass, he found Typhenie’s phone and one of her socks. Her keys were still on top of her car, where she and Chris had first been talking.

According to Asher’s later testimony, he called Chris and demanded he come back: “You’d better get back here right now.”

“It sounds like you’re blaming me for something,” Chris countered.

When Chris didn’t return after 15 minutes, and Typhenie remained unreachable, Asher’s girlfriend called the police. Upon their arrival, Asher called Chris again and the responding officer took the phone and ordered him to return. According to the affidavit, Chris returned about 25 minutes later, sweating profusely, and alone. It had been about 90 minutes.

It was hot out, Chris explained when the officer asked why he was sweating. It was a cool Monday evening, 64°F.

The officer recorded his conversation with Chris. “I’m feeling like everything’s being stacked against me,” he said. “You’re taking my car. I don’t know how I’m going to get home. I don’t know if I’m even going home.” He denied having harmed Typhenie and denied having backed his car up to the grass as Asher had said.

Chris was arrested that night. Law enforcement also searched the home he shared with his parents, about 20 to 25 minutes away. In the backyard, they found a bra with the clasp stretched out as if it had been pulled until it snapped, a woman’s shirt, a FitBit watch with a broken clasp, and a man’s shirt. It’s not clear who the items belonged to, but Chris’s parents said they hadn’t seen them before that night.

There was no DNA found in his trunk, and no blood found in the grassy area. Though there are security cameras at the apartment complex, they didn’t work at the time. In the space of an hour and a half, Typhenie was gone.

Immediately, Typhenie’s kidnapping was making headlines. It was being reported on all across the county, and her photograph on the news was soon paired with a mugshot of Christopher Revill.

In nearby Fort Worth, the Islam family were among the many people who saw his mugshot flash across the screen. At the sight of his face, Hadiyah Islam was flooded with memories. “I never thought I’d see him again,” she says. It had been 10 years since Chris was a part of their lives.

The family heard the story Chris told the cops on the night of Typhenie’s disappearance: she got into a car with someone and left. Hadiyah describes the feeling that came over her as instant recognition, like a bell going off inside her mind. That’s exactly what he told us [about Taalibah], she thought. He did it again.

Ten Years Gone

When she talks about her little sister, Hadiyah Islam is calm and measured. She has had 14 years to find ways to put her grief to words, 14 years to adjust to the empty place in her life. Her little sister, Taalibah, was full of light.

“She was the class clown all the time,” she recalls. “Always had a smile, always making jokes.”

Theirs was a close-knit family, born and raised in Fort Worth. Taalibah was the youngest of the three Islam sisters, but she was also the tallest. In a picture of Taalibah at 15 years old, she is standing with their father, wearing a red dress, heels, and a huge grin. Their heights are just about equal.

“She was real tall, the tallest out of all three of us and the skinniest,” Hadiyah says, a smile in her voice. “Everyone called her ‘Slim.’ [She was] crazy tall, crazy skinny with this big old smile.”

For 14 years, Hadiyah has acted as the spokesperson for her family, doing countless interviews with reporters and podcasters, trying to keep Taalibah’s name fresh in people’s minds. “I was the type—I never thought it would happen to my family,” she says.

Then came Chris Revill.

Taalibah, as she remembers, knew him from attending O. D. Wyatt High School. Sometime after high school, Chris and Taalibah got back in touch and started dating. Hadiyah doesn’t remember now what brought them together. It was a long term relationship, at least two years, but what Hadiyah remembers most, is the way it disintegrated as Chris grew violent.

In 2005, a Fort Worth Police Sergeant took a disturbance call at Chris’ house. Years later, during his sentencing, that officer would testify that Taalibah said Chris had assaulted her when she was nine months pregnant with his child by punching her in the stomach and head.

“Toward the end, I know my mom could not stand him at all,” Hadiyah says. “I really didn’t remember this until years later, but she remembers that [at one point] Taalibah had a restraining order against him.”

In late 2005, Taalibah gave birth to a son. When Chris came to the hospital, Taalibah and Hadiyah’s mother stopped him. She ordered him to leave and to stay away from her daughter.

The family could keep Chris away from themselves, but they couldn’t force Taalibah not to see him. Taalibah and Chris were still trying to make it work. Abusive relationships aren’t so easy to leave especially when there is a child. “You want to leave so many times but something pulls you back in,” Hadiyah says. “You think things are going to be different, but it never happens. It’s a circle, a never-ending circle of lies and abuse.”

By Jan. 16, 2006, Taalibah and Chris were not living together, but were not broken up. It was a Monday, and Taalibah went to Chris’s house to drop off their 3-month-old son so Chris could spend some time with him.

Later, the Islams would find out terrifying details about what happened that day from witness testimony. Chris’ own sister, identified only as K. Revill, would testify in 2019 that she was present in the house, a witness to one, last, terrible fight between Taalibah and Chris that ended with him punching her so hard that Taalibah screamed, “I think you broke my jaw.”

Taalibah’s best friend, Christina, would also tell Hadiyah and police that on that day, she received a tense, whispered call from Taalibah while she was at Chris’ house, asking Christina to come pick her up.

But no one would hear from Taalibah again.

About a week later, Hadiyah received a call from Chris who told her that Taalibah had left their child with him and hadn’t returned, and he couldn’t take care of their son. Taalibah’s radio silence wasn’t completely unusual. Sometimes when their fights were especially bad, Taalibah would leave to cool off. She had a lot of friends, lots of places where she could be regrouping.

“Taalibah was always around people,” Hadiyah says “For me to think she up and left—I thought they had an argument and was trying to cool her head.”

Hadiyah and her family took in Chris and Taalibah’s son, and they waited for Taalibah to return. “She would leave, but she always returned.”

There was one ironclad reason why the Islams knew that Taalibah would come back: her son. When he was born, Hadiyah recalls, they all saw that something in her changed, and refocused around him. “She calmed down. She just wanted to be a mom,” Hadiyah explains.

Chris filed a missing person’s report 16 days after the day Taalibah came to drop their son off. The responding officer took his simple statement: Chris said that Taalibah was at his house around 8 p.m. to drop off their son. She then “exited the residence and got into the general vehicle,” which he described as a dark green four-door sedan. He told the police that he did not know who the vehicle belonged to.

Two weeks turned into three, and then into four. The Islam family, who had lost all contact with Chris the day he passed them his son, were left without answers. Chris moved out of his old place. There were no leads, very little coverage, no wide, organized searches, and Chris wasn’t investigated as a suspect. Years ago, an acquaintance of the Islams who worked at the DMV looked up Taalibah’s information. None of it had been used since her disappearance. All anyone knows is that Taalibah never came home.

“I’m still wondering, Did I do this right, did I do that right,” Hadiyah says. At the time, she was in her early 20s. “Looking at the way it is now, I would have taken everything about Taalibah and Chris more seriously.”

For 10 years, the Islam family searched for Taalibah. They printed fliers and shirts, and posted her picture everywhere they could. On one 4th of July, they wore shirts with Taalibah’s picture, that read “Taalibah, please come home.” Passersby stopped to ask what it meant and were shocked by their story. It was a struggle to get the word out. Hadiyah points out that even at Typhenie’s trial, she spoke to someone affiliated with the courthouse who was surprised to find that Taalibah was still missing. “I thought they found her,” they said.

Chris and Taalibah’s son turns 15 this year. For most of his life, Hadiyah and Taalibah’s oldest sister has raised him as her own. He was born four months apart from her biological daughter, and the Islams always knew that one day—a day they dreaded—they would have to tell him. About a year ago, the day came and they still wish there had been some way to shield him from the pain.

Taalibah’s case was cold for 10 long years. Without any leads, the Islam family learned to bear life without her as they continued to search.

In 2016, Christopher Revill met Typhenie Johnson.

Retracing Steps

After seeing Revill’s mugshot on the news, the Islams came forward with their daughter’s story. Janelle says finding out that another girl had been missing for 10 years under such similar circumstances was horrifying. None of them knew about Taalibah. Typhenie hadn’t even known Chris had a 10-year-old son living in Fort Worth.

“They’re a part of our family now,” Janelle says.

The families have searched thousands of acres in Euless and Fort Worth from Sandy Lane Park, which is right next to the Revill home, to Lake Arlington, to the open spaces between Cook Lane and Highway 183. It’s full of pockets of forested land that is reshaped constantly by bad weather and the roaming of wild hogs, foxes, and other scavengers.

These searches are based upon careful planning and educated guesses, but they rely on hope and luck. In the case of Christina Morris, another young woman from DFW who vanished in 2014, groups conducted weekly searches in the areas where it was presumed she may have been hidden. It still took three and a half years for a construction crew to uncover her—in an area that had been searched at least twice before by her father and volunteers.

These are the same odds that the Johnson and Islam families face. Paula Boudreaux, a local private investigator, is one of the people closest to the investigation, and she thinks of these factors all the time.

The first five or six missing persons cases Boudreaux worked were successful. These were cases where the missing party was running away or leaving under their own steam. She found doors that opened for her when they wouldn’t for law enforcement and learned that when a timeline is 24 to 48 hours, there are always signs, always a trail to follow; a destination dug out of browser history, a note left in the trash, a receipt for a rental car. But these cases were nothing like Typhenie Johnson’s, much less Taalibah Islam’s.

“Basically, you’re putting a puzzle together,” she explains. “Sometimes you have all the pieces and sometimes you don’t. Taalibah and Typhenie, we have a lot of the puzzle pieces but we’re missing the one: where are they?”

The cases, in method and suspect, are nearly identical. Both romantic relationships were troubled and both are still missing. Even his excuse is the same both times. But for all their eerie similarities, they have unfolded in very different ways. With Taalibah, Chris was in complete control of the situation for a full week. No one knew she was missing, and he got to make the report, giving him control of the alleged crime scene and later, the story. There was time for tracks to be covered. But with Typhenie, he only had 90 minutes, and off the bat, he was considered a person of interest, not a concerned boyfriend.

“We know who he called. We know he had a set amount of time, and we know where his cell phone pinged,” Boudreaux says. If he had helped, it would have had to be premeditated, and she has a different theory: this was an impulsive, angry decision that from the start had gone wrong.

“I think Chris is a person who, when he gets angry and is pushed to the limit, he strikes out,” she says. “Most people, if you look at killers so to speak, murderers, the ones who do it just one, there’s something that snaps in their brain. They get so angry, snap and strike out, when an incident occurs. In a way, we all have that in our bodies. If your life is on the line, you will fight back. You will fight to the death.”

A former psychology major, Boudreaux tries to put herself in his shoes and state of mind, considering what could drive him to do what he did. It’s already known that he and Taalibah had been embroiled in a fight that had turned violent. On the evening of her disappearance, Typhenie was arguing with him. He knew that Typhenie had moved on, and was in fact, eating dinner with another man that evening. And something snapped.

“He may not even remember,” she says. “It’s almost like a drunken syndrome. You can be smashed out drunk, say ugly things, not remember what you did the night before. The next morning, people are pissed at you and you can’t remember what you said.”

She imagines that Chris didn’t expect to be questioned and arrested so quickly. There is evidence that couldn’t be hidden. For example, leaves were found on his floorboards and plant stickers in his tires. That tells Boudreaux he likely drove through grass or brush.

During the trial, arresting officer Det. Pat Henz described his interaction with Revill that night. "He mentioned that he loved her. That they were in this relationship but at that moment he said, ‘that girl,’ referring to her as, ‘that girl’ and the rest of the entire interview never used Typhenie’s name. Never called her by name, never said anything other than she or if I said Typhenie,” Det. Henz said on the stand.

Boudreaux has concluded that if Typhenie is dead, then she is close to the apartment. Her theory is that if that is the case, she would have to be hidden on his way back to the apartment.

“The question becomes, did he take her somewhere, drop her off at someone’s house? It’s difficult,” she says. “You’d think it wouldn’t be because there’s not much of a timeline.”

Whatever happened to Typhenie, wherever he put her, she thinks it was meant to be temporary. He didn’t know that he would be arrested, unable to secure her somewhere better. In Taalibah’s case, he had time to cover his tracks. For that reason, she doesn’t believe they are together.

“It’s possible, but you’re talking about a wide period of time that went by,” she says. “Chris had their son. He reported her missing. He got away with it for more than 10 years, so it would have to be an area that is not disrupted by construction over the years.” She remembers another missing girl in Lubbock. The guilty party bought fast-drying concrete and poured a new back patio with her body inside.

For now, her best course of action is to retrace his life and keep looking for that one little clue.

Life Sentences

The trial of Christopher Revill for the aggravated kidnapping of Typhenie Johnson was a two-week long slog in the heat of August 2019. Day after day, members of the Islam and Johnson families were in attendence. The prosecution called 28 witnesses, from Typhenie’s brother, Asher, to state experts and police investigators, all pointing toward one conclusion:

“You see a man who is obsessed with Typh, a man who a month earlier said he wanted to marry her,” the prosecutor, Lisa Callaghan, said of Revill in her closing statement. Revill, she said, kept over 200 photographs of Typhenie. When he knew Typhenie was moving on, he couldn’t handle it. “He was not going to let her go.”

The defense called only two witnesses, but their defense was no less passionate. His attorneys attempted to throw the case out on a Brady violation: alleging that forensics which found none of Typhenie’s DNA in the trunk of his car was not shared with them. This evidence, they argued, is exculpatory. They are now working on appealing the case.

“We submit to you that the state put forth a very incomplete case,” Lesa Pamplin, one of the defense attorneys, said. “If there’s gonna be a struggle and she’s struggling. There is none of her on his shirt, none of her on him.”

The defense says investigators never considered other suspects. The prosecutors answer that Chris is the only suspect who makes sense. Without any sign of Typhenie Johnson, the jury had the difficult task before them, of ruling on a case that will feel open-ended until she or her body come to light. After over six hours, they returned a guilty verdict.

However, while the case was focused on Typhenie, the sentencing, for the first time, shed light on Taalibah. The Islam family finally got the chance to tell her story in court, and the similarities between the cases were clear enough that Revill received life in prison with a possibility of parole in 2046. Janelle Hofeldt has the date seared in her mind. If she’s around, she says, she will be at his parole hearing, fighting to keep him off the streets.

For the Islams, it was an echo of justice for a crime 14 years cold. But, Hadiyah told the press, justice for Typhenie was justice for Taalibah. “I still feel my sister,” Hadiyah said.

It’s a cruel twist, but if Taalibah’s case had been solved, Typhenie likely would still be with her family, spoiling her niece like crazy; yet if Typhenie had never gone missing, the Islam family would still be the only ones searching for Taalibah.

“This would not be possible without Typhenie,” Hadiyah said through tears after the sentencing. “I hate to say that but it’s true.”

In June 2020, remains were found on a piece of private property in Fort Worth, and the Johnson and Islam families held their breath. Friends sent well-wishes and prayers, and from Minnesota, Janelle waited for news and asked their Facebook friends for patience.

Then the news hit: the body was male, neither Taalibah or Typhenie.

“I was relieved it was not her,” Janelle says. “I know Typhenie’s mom was relieved, but at the same time, there was grief because it’s another human who lost their life for what reasons. Every time we hear there are remains, you’re sitting on the edge of your seat, waiting for this news and then you find out it’s not. Like I said, relief but grief.”

But on the other hand, another family out there has closure. They can put their son to rest. The Islams and the Johnsons don’t have even that opportunity. There are pictures of Taalibah everywhere in the Islam’s homes, and Taalibah’s nieces and nephews are full of curiosity about her, hungry for stories of her life. Only one of her children even had the chance to meet their aunt. Hadiyah’s oldest daughter was a toddler when she vanished.

Rather than dwell on the terror of her absence, for their sake Hadiyah tries to remember her sister for who she was, for her energy and magnetism, her goofy antics and the ways she made her laugh. “I think about good times, but you have those moments where you think about the bad times too,” she says. “But I don’t want the bad times to overshadow the good.”

In the four years since her disappearance, Typhenie’s family has also struggled to move on. Her mother and brother both live in Euless, Texas now. Typhenie has a 1-year-old niece who she has never met now. In the apartment where they live, Typhenie’s presence is everywhere. Her favorite animal, elephants, dance on their shower curtain. Asher gave his daughter Typhenie as a middle name. “Looking at pictures between her niece and Typh, they look identical,” Janelle says with wonder in her voice. “Typh’s a shopper. She would spoil her niece rotten.”

Janelle says that they have not lost hope for Typhenie’s safe return. “That’s what our family is like. We won’t give up.” Along with a reward for information, any donations go into a bank account in her name. If Typhenie is found alive, Janelle says, she’ll have support for whatever she needs. Janelle believes that Typhenie is alive. It’s an echo of Paula Boudreaux’s philosophy: “Until I have a body, I never believe anyone is dead.”

The Islam and Johnson families never should have known each other, but they’re now forever connected by tragedy. Janelle says she considers the Islam family part of her own now. “We aren’t just looking for Typhenie,” she adds. “We’re looking for Taalibah. Three and a half years has been absolutely hard to deal with. I can’t imagine waiting 14 years for answers.”

Hadiyah admits that it is exhausting, but that she can’t stop. “I want to know where my sister is,” she says. “Even though it’s tiring, I’m going to do as much as possible. Both of our families need closure.”

“We won’t give up,” Janelle says. “We just want them home.”