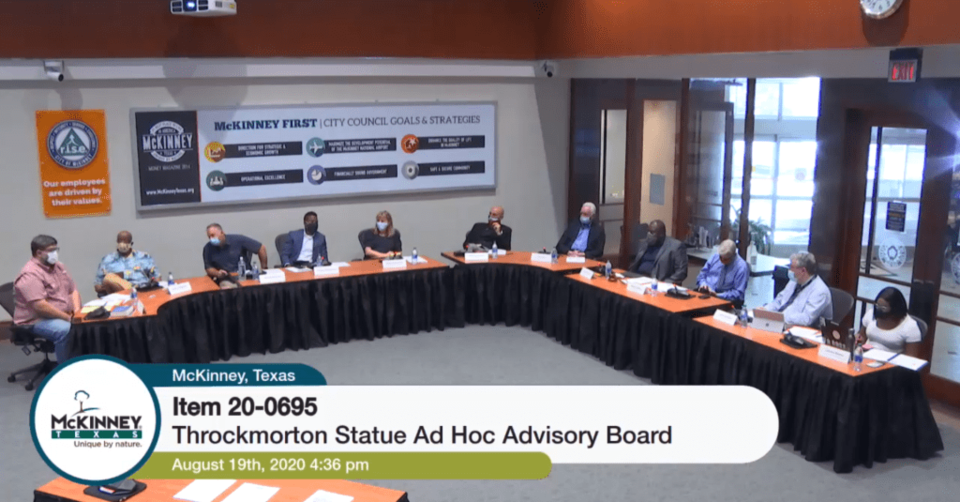

Before the meeting begins, McKinney City Manager Paul Grimes reminds the 11 gathered men and women what they are there to accomplish. "This is what communities are about," he says. "Turn the temperature down and have a thoughtful approach."

For the first time on Wednesday evening in mid August, the 11 members of the new Ad Hoc Advisory committee are meeting to discuss a statue of Gov. James W. Throckmorton and its placement in the downtown McKinney square. The members include business owners and one former judge, as well as representatives from the Arts Commission Board, the Historic Preservation Advisory Board, the McKinney Main Street Board, and the Collin County Historical Commission.

It won’t be the board’s decision whether or not the statue will stay or be removed. Instead, their role over the course of the next few weeks is to guide the efforts of the city staff as they take a thoughtful approach to the debate. It’s what Grimes describes as “a delicate subject that involves race and equality.”

The public will have the option to have their concerns heard; the third meeting, September 17, will be a public input session. Once the advisory board has had a chance to review all the information, they will present their findings to the city council, but will not present a recommendation of what to do. That will be McKinney City Council members’ decision.

The first meeting is supposed to be about the history of the statue, of Throckmorton himself, and the rules for antiquities and landmarks. A few interesting details emerge, for example, that Throckmorton’s statue was not sculpted by Pompeo Coppini as originally thought. Its artist is unknown.

But as Guy Girsch, the historic preservation officer, and Mark Doty, assistant director of planning, present context to the statue, it becomes clear that the issue of the statue will be a complicated one. The board has mixed opinions on whether or not the statue should be considered an official Confederate monument, meaning one sponsored directly by the Daughters of the Confederacy.

Collin Kimball, one of the board members, provides a wealth of information about Throckmorton. He says that there are no historic documents tying the statue to the Daughters of the Confederacy. And while it may not be considered an official Daughters' statue, the library did find newspaper evidence that the Daughters did eventually take over the fundraising in 1910 and contribute donations for the statue.

Kimball also mentions Throckmorton's advocacy against secession and joining the Confederacy, but board member Justin Beller isn’t convinced and instead argues that opposing secession is not the same as opposing slavery.

"The mentality about being against secession … he was against it because of economic reasons, not because he was opposed to slavery in any way," Beller says.

As Kimball explains, Throckmorton was part of a class of people in Texas who migrated to the state before it was a part of the United States and still the Republic of Texas. "They had fought so hard to be part of the Union. They were also landlocked and needed the resources of the Union which was why he was against [secession], not because of any moral high ground about slavery. It’s real clear. He owned one slave. That’s the framework."

Committee member Kenneth Holloway adds, "We have to consider intent … He was not in support of abolitionists but was against separating from the Union for practical reasons."

"I am somewhat uncomfortable about comments being made that I would like to see the evidence — just this last thing for example," Judge Nathan White says. "I’m used to seeing evidence as opposed to allegations."

As the conversation continues, it turns to the legalities that would be involved in taking the statue down, considering that it is a state landmark, but it sits on city property.

"If it’s a state landmark, are we wasting our time?" Kimball adds. "What are the rules given the dispensation of that statue?"

A city representative explains that they would need to submit a permit to the state to remove the state antiquities landmark, just as Denton recently did.

Discussion turns personal when Holloway turns to Kimball and asks a very pointed question about the research packet on Throckmorton that he provided to the council: "I noticed that the text referenced ‘hostile Indians’. I was perplexed — why was it written that they were considered hostile?"

"They were attacking settlers," Kimball replies.

"Was it their land? Were they trying to stand their ground?" Holloway pressed him.

"I can’t answer. I can only say that we all grew up watching movies of the wild west, and this was the edge of the wild west."

"It’s probably a question you can’t answer," Holloway says, "but I want it to be noted that when we use words like hostile to describe people defending land that to them was theirs, it can show some bias."

Again, Beller points out, this question is one of context. When it comes to discussion of the "lost cause," or the idea that the Confederacy’s cause was a just and noble one, he says, language can be a powerful weapon. He says the board should be careful of the "language we use to describe what was white supremacy at the time." As he sees it, the statue "correlates all the other statues in the area in terms of timing, intent, and purpose."

White is less convinced. The plaque on the statue, he says, does not mention the Confederacy or even Throckmorton’s short-lived run as governor. “It makes a big difference to me,” he says. “It can’t be a confederate memorial if it doesn’t have anything to do with the Confederacy … there is no evidence whatsoever in that particular structure to indicate that it is connected with being governor or being a Confederate.”

“I empathize with [Holloway’s] point, because I am also a descendant of a slave,” Kimball, who is white, says of Holloway, who is Black. “My grandfather was enslaved by the Emperor of Japan as a prisoner during WWII and he barely survived. You have a good point. But this is not a Confederate Monument, not endorsed by Daughters of the Confederacy then or now. It was a memorial built by the people of Collin County because as a statesman, no one achieved what [Throckmorton] did, warts and all.”

Holloway pauses to think. “Jeffery Epstein could have done a lot of great stuff for people, but would you be okay with a statue of him?” he asks. “...I put Throckmorton in the same boat. You can say it’s not a confederate monument and maybe it’s not. But then you have to go with the man. It’s just does the man deserve to be in a public square? Can he not go somewhere else?”

Jimmy Stewart, one of the board chairs, counters: “At some point in a free society there are some things we’ll be offended by and that’s part of being free. You can’t satisfy everyone.”

White wonders if this statue is taken down, where does it end? As a Vietnam veteran, he asks, would people one day come for his monument? Beller replies that statues are taken down all the time. "The South lost this war. We’ve created monuments in that memory. This isn’t an American monument, this is a Confederate monument."

In the second and last city presentations of the meeting, the city staff defines monuments and memorials as "public art with political and social purpose" and points to examples like Mount Rushmore and the National Memorial for Peace and Justice in Montgomery, Alabama, which memorializes the legacy of Black people who have suffered acts of racial terror like lynchings.

Beller notes that one of the lynchings memorialized there occurred in Collin County. He is referring to the lynching of Commodore Jones in Farmersville that occurred the same year the Throckmorton statue was erected.

According to various papers at the time, and the Lynching in Texas records page, in 1911 Commodore Jones allegedly insulted a white woman over the telephone. He was arrested in Farmersville, and though a sheriff from McKinney attempted to collect him, due to the threats from the mob, he returned home without him. That night, a mob of 75 men and boys dragged him from his cell and made him climb a telephone poll in the public square. At the top, one of the men put a noose around his neck and forced him to jump. The newspaper reports that according to his employer, Jones was "a trusty negro," and that "the town is quiet tonight."

Within six years of the incident, Farmersville put up a Confederate monument of an anonymous soldier, a symbol of the lost cause.

The city presentation ends with a quote from the American Historical Association: "A monument is not history itself; a monument commemorates an aspect of history, representing a moment in the past when a public or private decision defined who would be honored in a community’s public spaces."

The meeting is nearing its end when Holloway makes one last pointed remark at White. "I have a question for you. It hit me as you were talking, correct me if I’m wrong but it appears to me that you have a tough time having empathy for people who don’t look like you …"

"You should be careful about proposing what you think people believe in their heart," White interjects.

"If it was your people who were oppressed and enslaved and lynched—and you saw a statue of a man and it reminded you of that past and that past for you doesn’t feel so pleasant," Holloway says. "I know white people may not see it the way I see it. As a fellow citizen, I would ask that you listen to the concerns and the pain I’m telling you it causes me and people who look like me. … I’m asking you to empathize and say I hear what you’re saying, I hear your concerns, and I want to go my part to help make unity. What would it hurt if it went somewhere else?"

The meeting concluded with a promise to bring forth more research in the next meeting on September 2.